King Arthur and the Languages of Britain

Why do some historians claim that Arthur never existed?

My latest book came out with Bloomsbury as an ebook last week and Substack recommends that authors devote a post to their new books when they are published. So here goes.

Why did I write King Arthur and the Languages of Britain? I did it because there has been a lot of very poor academic writing on King Arthur in recent years.

I’ve been writing on the early languages of Britain since the 1990s – I’m a specialist in historical linguistics – but most medievalists do not seem to know how to use linguistic evidence properly. So my book sets out how linguistic evidence can be used to aid historical understanding and what principles should be used. I focus especially on mistakes made by historians who have graced us with screeds on why they think King Arthur never existed.

I always try to be open-minded about these kinds of things and I was mainly interested in what the evidence records, not trying to prove whether Arthur existed or not. But most Arthurian sceptics don’t seem to understand how to assess older written records.

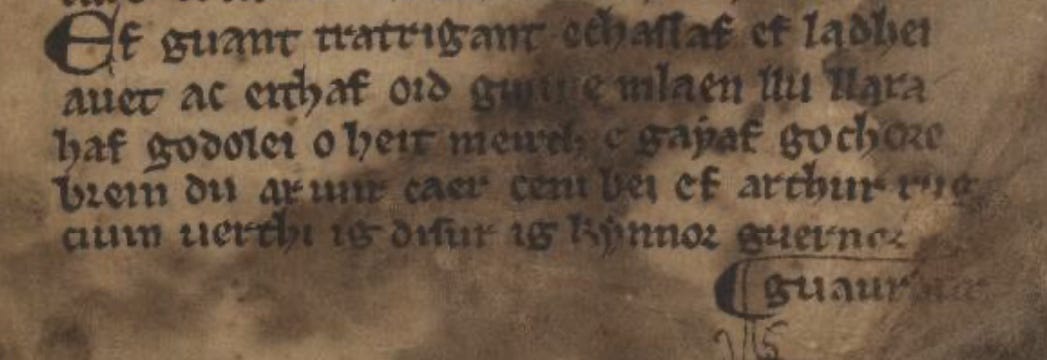

There are only two early sources that mention Arthur that provide specific details about him and the manuscripts they are preserved in date from many centuries later. But the two sources are both full of linguistic evidence that indicates they preserve genuine, sixth-century records. This evidence has been ignored for half a century, but some of it is very basic and easy to recognise.

One source, the Welsh annals (or Annales Cambriae as they are known in Latin), begins with entries on events that occurred during the fifth and sixth centuries, including two mentions of Arthur. The annals are written in Late Latin – the Latin used by people like St Gregory of Tours in the sixth century. But its long not been recognised that the Latin of these entries is of a typically sixth-century type.

A lack of linguistic sophistication has long been a problem with the work on the earliest sources that mention Arthur. The study of these records has been sullied by assumptions made by people who lack the necessary linguistic skills to judge how old the records they were dealing with are.

But I didn’t set out writing King Arthur and the Languages of Britain as a response to what previous historians had claimed. I started out not even intending to write a book on King Arthur.

My original idea was to write a book on the languages of Britain that showcased two significant discoveries.

The first occurred after Roger Tomlin, a retired lecturer from Oxford, approached me for my opinion on the Uley tablets. His much-delayed book on the Uley inscriptions has only just appeared. But two of the inscriptions from Uley, an obscure archaeological site in the Cotswolds, preserve a series of linguistically Celtic sentences from the Roman period. It took me two months to decipher them and they are pretty exciting if you are interested in the early development of languages such as Cornish and Welsh.

The other was my decipherment of Pictish. I’d first looked at the Pictish ogham inscriptions closely over ten years ago and realised that I could make sense of them. People have been trying to decipher Pictish for over a century, but most of the attempts to translate the inscriptions have been quite unorthodox.

Both the Uley inscriptions and Pictish seemed too big a topic for another academic paper or two, so I started thinking about a book. But the title I’d been thinking of, “The Languages of Britain in the Arthurian Period”, seemed to be missing something – a certain king.

So I thought I’d better look at the sources for King Arthur again – thirty years after I’d first encountered them – to see if I could say anything of interest about them from a linguistic perspective. I quickly realised that no one with sufficient linguistic skills had tried to analyse them before.

This was particularly the case with a famous essay by David Dumville, an English historian who passed away last year. Dumville was a contrarian and rather erratic. But his dismissal of King Arthur as a legendary figure is widely set as required reading for university students. Dumville claimed that people who believed that King Arthur was a real figure belonged to a “no smoke without fire” school of thought. But Dumville lacked the linguistic competence to understand what was going on with the Welsh annals.

The publisher has, unfortunately, set the initial price for King Arthur and the Languages of Britain much higher than I expected. But hopefully it will be reduced when they release a paperback edition.

I hope that the cover will prove more attractive. It was inspired by a visit to the William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow in north-east London. It’s a great museum if pre-Raphaelite design is your thing and it is much more rewarding than reading jaded academics moaning about the public’s continued fascination with all things to do with King Arthur.

I’ve also just been told that I’ve been awarded a fellowship to visit the Centre for Arthurian Studies at Bangor University in Wales. So I’ll be sipping the mead at the centre of the Arthurian world for a bit later this year and we may even get the chance to follow the Merlin trail up to the top of Dinas Emrys.

Congratulations. I hope your book proves to be a great success and reorientates thinking.

I found this historical piece very interesting especially with your claim about deciphering an ancient language. I particularly love that about the story, I guess we have that in common, I specialise in cracking ancient code, I have an interesting take on King Arthur myself. Best of luck with your work. I will definitely be checking out the paperback.