Understanding Pictish

Deciphering the Bressay and Lunnasting inscriptions

Everything to do with the Picts is a national question. The Picts are very dear to the hearts of Scots, with good reason. But their language has long been perplexing. In the nineteenth century, linguists debated whether Pictish was a Celtic language, closely related to Welsh, or something altogether different. By the 1950s, the consensus was that the language recorded in the Pictish inscriptions was not related to Welsh – all the main experts in the Celtic languages agreed. But what was Pictish precisely?

The problem with trying to analyse Pictish is not that so many people have tried previously and failed. Pictish has been argued to be related to Welsh, Scottish Gaelic, Basque, Finnish and even Old Norse. Reviewing a widely-criticised attempt to interpret the Pictish inscriptions as Old Norse, the runologist Michael Barnes offered the following characteristics as typical of a successful proposal:

Solid evidence must be brought to bear to show why it is better than previous hypotheses; there have to be objective means of testing the evidence; counter-evidence needs to be carefully considered – and rejected only for clear and valid reasons; and, not least, the hypothesis must be subject to constraints: where anything is possible, nothing is probable.

The main problem with analysing Pictish has been where to start. But the answer to that question is “with its morphosyntax” – its grammar and word order. And key aspects of the morphosyntax of Pictish seem to be revealed in the inscriptions from Bressay and Lunnasting, both of which were found in Shetland and were first assessed in the nineteenth century.

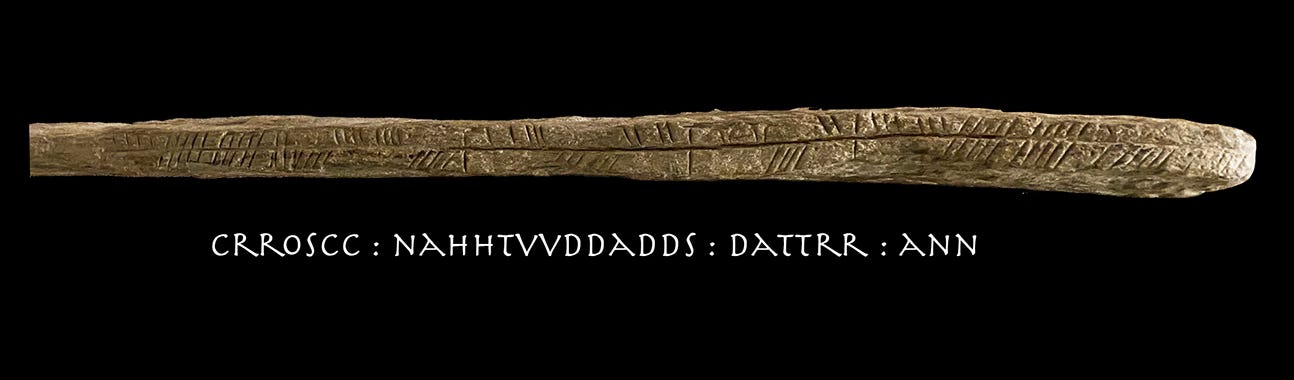

The most important Pictish inscription from a linguistic perspective has long been acknowledged to be that preserved on a stone from Cullingsburgh, Bressay, conserved today in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. It was first noted in 1853 that the Bressay inscription begins with an ogham sequence crroscc, comparable to Latin crux ‘cross’, and it is recorded on a standing stone with a cross engraved on it – both on its front and back. The reference to the cross is then followed by a name Nahhtvvddadd that has an s attached to the end of it as if the first two words mean ‘Nahhtvvddadd’s cross’. The inscription then seems to continue on the other edge of the stone with a second name Bennise meqq Ddroann where meqq has long been supposed to be the equivalent of a Scottish Gaelic or Irish filiation marker mac ‘son’. But what is the second name doing on the stone?

The simplest way to analyse the Bressay inscription is to compare it with texts found on similar memorial stones. Runestone inscriptions typically record two names, with one name being that of the deceased person and the other the commissioner of the memorial. Runestones from the Viking period are so stereotypical, you can read the beginnings of most of them without knowing much Old Norse. They are relentlessly of the general form “X raised this stone in memory of Y”. One of the runestones in the park at Uppsala University, for example, reads Þiagn ok Gunnarr ræistu stæinna æftiʀ Veðr, broður sinn ‘Thiagn and Gunnar raised these stones in memory of Veðr, their brother’. It is reasonable to assume that the Bressay inscription is of this same basic type, with Bennise meqq Ddroann having set up the cross-decorated slab in memory of Nahhtvvddadd.

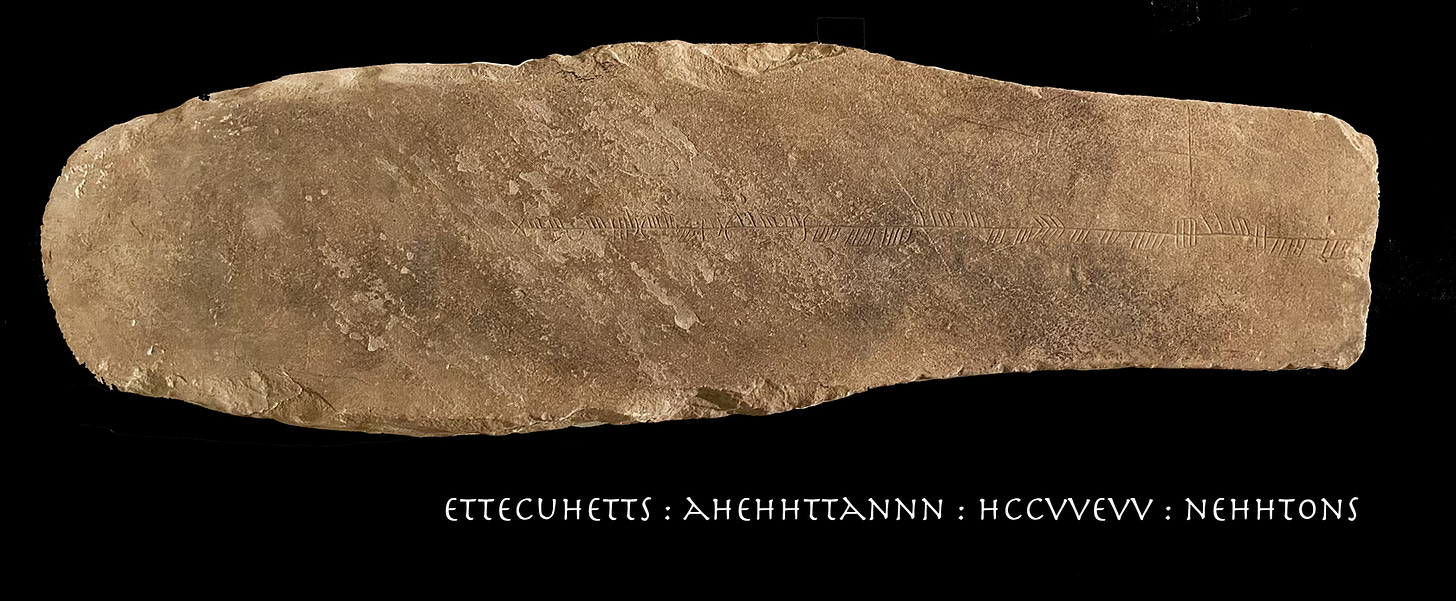

Another Pictish inscription that appears to mention two people comes from Lunnasting on Mainland, the main island of Shetland. The Lunnasting stone is also conserved in the National Museum of Scotland and its ogham inscription begins with another sequence ending in s and it ends with a clearer name Nehhton, also ending with what seems to be best read as an s. A similar name Nechtan is recorded as that of several Pictish kings and Nehhton appears to be much the same form. Rather than a crroscc ‘cross’, however, the Lunnasting inscription seems to refer to the object it is recorded on as an ette. The term ette is recorded in several of the Pictish inscriptions and it seems likely to be the equivalent of the formulaic Old East Norse term stæinn ‘stone’.

So the inscription on the Lunnasting stone seems to be syntactically much like that from Bressay. But what about the rest of the two inscriptions? What do the middle bits mean?

It has long been speculated that the sequence dattrr that comes after the name Nahhtvvddadd on the Bressay stone is a loanword of the Old Norse term dóttr ‘daughter. But why would an Old Norse ó become a in Pictish? Pictish clearly had a sound o – it’s attested in crroscc ‘cross’, the name Nehhton and in the patronymic meqq Ddroann. The Pictish term dattrr may just be a different word that only looks a bit like Old Norse dóttr.

A more revealing way to approach the middle section of the two inscriptions is to consider what they have in common. Many inscriptions have been deciphered by linguists by comparing their formulaic features. Italian linguists call this approach the “combinatory method” and use it to analyse inscriptions written in Etruscan.

The Bressay inscription preserves a word ann precisely where the Lunnasting inscription has a sequence annn. It’s likely they are the same word and that they have a function comparable to Old Norse ræistu ‘raised’. In other words, the two inscriptions appear to record much the same message: ‘Nahhtvvddadd’s cross … raised Bennise meqq Ddroann’ and ‘Cuhett’s stone … raised … Nehhton’.

The only problem with this analysis is that both Bennise and Nehhton appear to have an s at the end as if they are genitives like Nahhtvvddadds and Cuhetts. There are two ways of explaining this. Either ann is a verbal noun indicting something like ‘(the) raising’ or the s indicates the agent of ann. If ann is a verbal noun, ann Bennises would mean ‘Bennise’s raising’ (or the like), but if the s is indicating the agent, ann Bennises should mean ‘raised by Bennise’. Either meaning would be functionally the same, but ‘raised by Bennise’ is more expected from a cross-linguistic perspective.

So it’s possible to translate most of the words preserved in the Bressay and Lunnasting inscriptions. The only difficult terms are dattrr, ahehhtt and hccvvevv. The first, dattrr, appears as if it may be an adverb comparable to Old English þæder ‘thither’ and hccvvevv has been assumed to be a title of some sort such as ‘king’ or ‘vassal’. The best translation of the Bressay inscription seems to be ‘Nahhtvvddadd’s cross, raised here by Bennise meqq Ddroann’ and the Lunnasting memorial is presumably best understood as ‘Cuhett’s stone, raised … by Lord Nehhton’.

But what does this mean for the linguistic analysis of Pictish? A few things are made clear about the morphosyntax of Pictish just by the Bressay and Lunnasting inscriptions.

The first is that s marks the genitive case of masculine names, just like English ’s. All the Indo-European languages used to have a marker of this type, but the Insular Celtic languages all replaced it with a palatal marker i. The only Celtic language which retained an inherited s-marker that is widely used with masculine names is Lepontic, the oldest attested Celtic language, formerly spoken in the Alps.

The second is that the s-marking does not seem to be Germanic. The word order ‘cross of Nahhtvvddadd’ and ‘stone of Cuhetts’ is not expected for a Germanic language. The Germanic languages are characterised by always putting personal names before objects in expressions like ‘Nahhtvvddadd’s cross’ and ‘Cuhett’s stone’.

So was Pictish some weird offshoot of Celtic or just a member of a different branch of the Indo-European family? The name Nechtan has often been proposed to be Celtic – there was even a Cornish saint with a similar name – and meqq appears much like the similar Irish and Scottish Gaelic filiation marker mac ‘son’. But no one has ever been able to explain Nahhtvvddadd as a linguistically Celtic name. The first element of Nahhtvvddadds looks more similar to the Gothic noun nahts ‘night’ than anything recorded in Celtic.

But the linguistic focus should be on the morphosyntax, not on the names. Grammatical markers are rarely borrowed from other languages, unlike words and names. English is full of loanwords – so much so that Old English often seems closer to German than Modern English. Names are also often adopted from other languages. Yet Modern English retains characteristic grammatical features such as ’s that it never lost and there is no reason why Pictish should be expected to be any different. Pictish shows characteristic evidence of being an Indo-European language, but not a Celtic or Germanic one.

Thank you very much; it’s fascinating. One question that springs to mind: are we sure we are transliterating the Pictish ogham inscriptions correctly ? How do we know the symbols had the same sound as in Ireland ? Especially if the languages in Ireland and spoken by the Picts are not similar. Isn’t it possible that the Picts borrowed the idea of ogham for their own writing system but attributed different sounds to the symbols. Even if the sounds are generally similar for ogham inscriptions in Ireland and those used by the Picts, it is possible that some are different if the languages are not similar. It’s not exactly analogous but look at the similarities and differences in the use of letters between the Greek and Latin or Greek and Cyrillic alphabets (albeit with Glagolitic intervening in the latter case).

Many thanks, this is fascinating, as always. My comment is probably very irrelevant, but it keeps coming back in my head, so here it is. When I read Nahhtvvddadd, I can't help read a nativitatis behind it. Which sounds odd, but given the presence of crosc, could it be a nativity cross?