Arthur and the Welsh annals

The Welsh annals preserve the earliest mentions of Arthur. But are they reliable historical records?

Anyone reading the academic literature on King Arthur will quickly understand the reason for the widespread scepticism about him. King Arthur was first made popular in the twelfth century by Geoffrey of Monmouth and Geoffrey was a fabulist. He relied on early historical sources, but he made up a lot of other details. There is no evidence that Guinevere or Uther Pendragon existed or that Arthur ever had anything to do with Tintagel Castle.

Geoffrey seems to have relied on Welsh folklore as well as whatever historical records were available to him. But two of the main written sources he obviously used have survived and historians have long debated how reliable they are. The main debate has focussed on how old the records are. The closer in date they were composed to the time Arthur ostensibly lived in, the more reliable their evidence is likely to be.

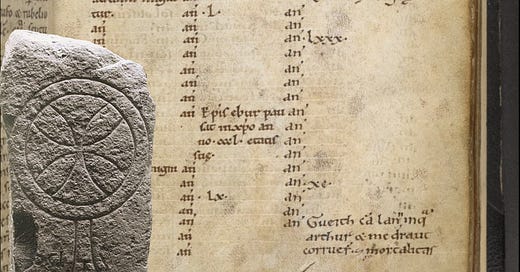

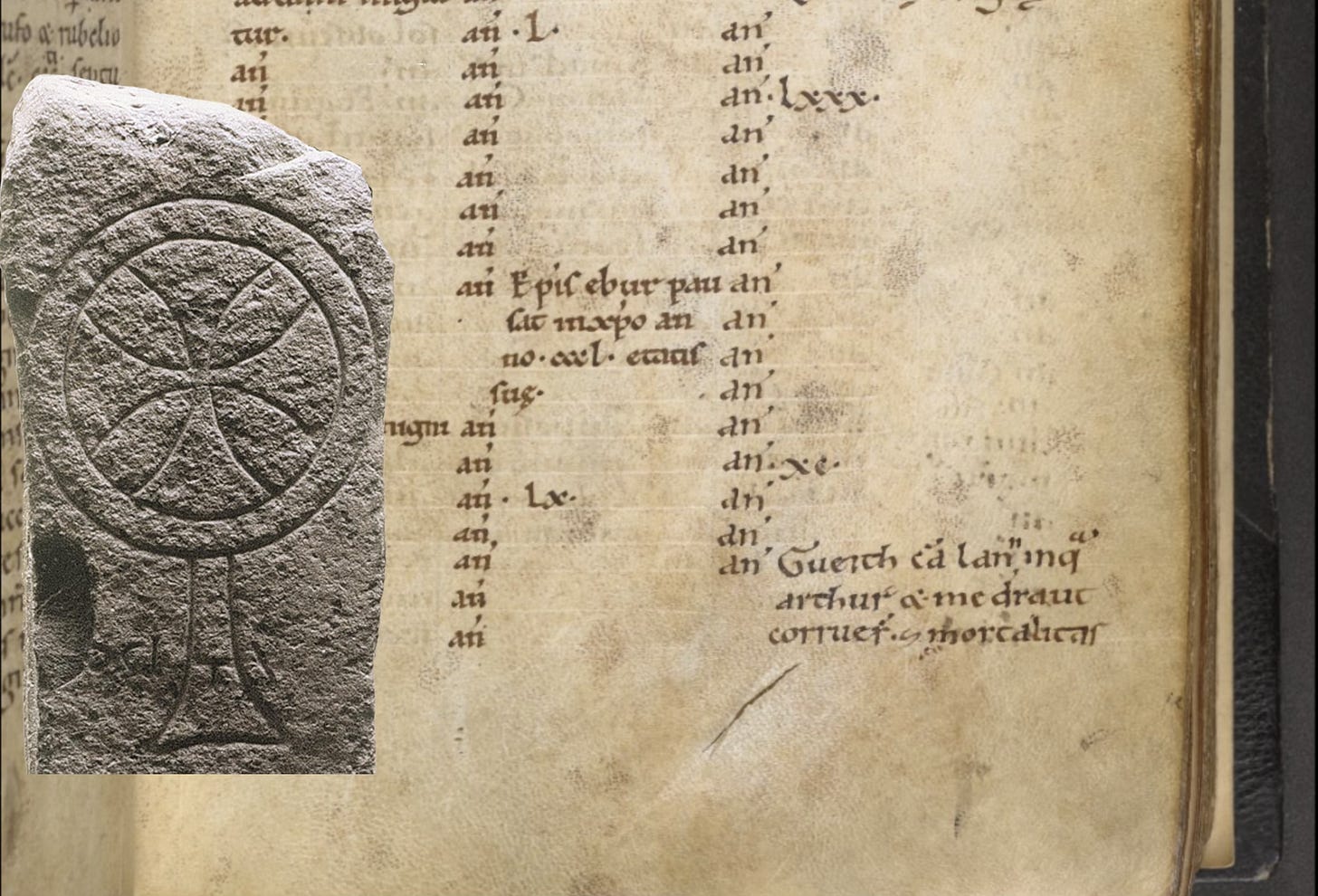

The oldest datable source that mentions Arthur is the Welsh annals – or Annales Cambriae as they are known in Latin. They are a set of annals of fifth-to-tenth-century date and they are known from three different manuscripts with considerable variation occurring between them. Two of the surviving copies of the Welsh annals include entries that date from after the time of Geoffrey of Monmouth, but the oldest copy of the annals preserves a version that is over a century older than the History of the Kings of Britain. It is conserved in the British Library and a digital copy of the manuscript was available on their website until it was hacked by a Russian ransomware group last year.

The Welsh annals seem to be a continuation of a chronicle that was originally kept in Scotland. The entries from the sixth to the eighth century may have been recorded at Whithorn, the oldest centre of Christianity in Scotland, while those from the late eighth and ninth centuries seem to deal with events occurring in the neighbourhood of St Davids in Wales. Whithorn and St Davids were leading religious centres at the time, so it’s reasonable to suppose that the records were created by monks or priests living at the two sites.

Some of the other entries in the Welsh annals seem to have been taken from Irish sources – they usually record the deaths of Irish saints, such as that of St Patrick. But what about the two records that mention Arthur? Where did they come from? They could have been entered at Whithorn during the sixth century. But historians have long just not been sure.

The fundamental question, however, is can the entries be trusted? Are they genuine sixth-century records or are they later concoctions?

Many people have looked at the records over the years and come up with all sorts of reasons to doubt the ones that mention Arthur. But by the 1970s, historians had got more and more confident that the entries were genuine. Why wouldn’t they be? Arthur’s name having a Roman origin seemed to demand it.

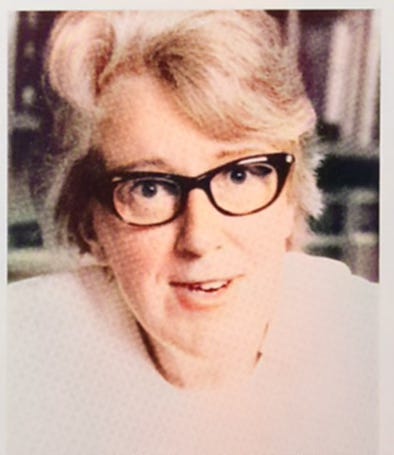

In 1973, however, Kathleen Hughes gave a talk to the British Academy in which she looked closely at the Arthurian entries. She decided that they weren’t reliable sixth-century records. Her reason was that the early entries in the Welsh annals are too spread out chronologically. They don’t look like the product of someone keeping a year-by-year chronicle, making notes of important events as they occurred. The entries from the seventh century onwards looked like genuine year-by-year records to Hughes, but not the ones that mention Arthur.

Hughes thought that the Arthurian entries were probably created sometime after the events that they record. She supposed that they may have been created as late as the eighth century. Her analysis was seized on by sceptics as evidence that Arthur had never existed – it was all made up. But was her analysis reliable?

Hughes hadn’t noticed a key issue with the sixth-century entries in the Welsh annals. It can be seen most readily in the entry that records the death of St Iberius of Wexford in 501. Translated from Latin, it records:

Bishop Ebur rests in Christ in the 350th year of his life.

There are two quite odd things about this record. The first is how long St Iberius is recorded to have lived. The entry seems to make St Iberius as long lived as a patriarch from the Old Testament. The Bible records that Noah lived for 950 years, Abraham lived for 175 years, Isaac for 180 years, Moses for 120.

The other unexpected thing is how his name is spelled. Why isn’t he called by his Latin name Iberius? He isn’t even called by his Old Irish name Ibar.

St Iberius isn’t quite as well known as King Arthur – unless you live in Wexford. There is still a church in Wexford named after him and a Church of Ireland school. St Iberius is recorded to have been one of the “four most sacred bishops” who lived in the time before St Patrick arrived in Ireland and the oratory he founded on Beggerin Island in Wexford Harbour may have predated St Patrick too. St Iberius must have been a real figure, although how old he really was when he died is not clear.

The way the name of St Iberius is recorded in the Welsh annals is not surprising if you think about it historically. His name was pronounced Ibar during the eighth and ninth centuries – and Iberius is just a Latinate form of Ibar. But Ibar is the expected Old Irish reflex of Ebur. Ebur is just an earlier form of the saint’s name – the one he himself would have used.

The preternaturally advanced age recorded for St Iberius also has an obvious origin. His age is given in Roman numerals as cccl and cccl can be understood as a number or an abbreviation. The Latin title clarissimus ‘most illustrious’ used of leading Roman officials is often abbreviated just to cl and cccl means ‘three most illustrious’. It looks like a scribe making a copy of the Welsh annals has just confused an indication that St Iberius was exceedingly illustrious with the number 350 and presumed that cccl was an indication that the saint had lived to an exceptionally advanced age.

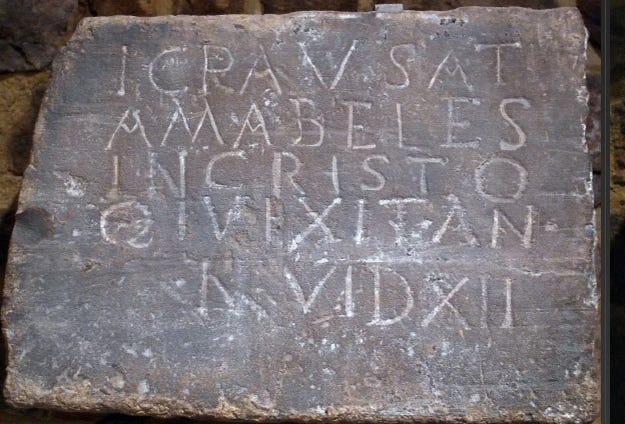

How the information about St Iberius got into the Welsh annals is the key question, however. Hughes thought the entry had just been copied from a much later Irish source, but no attested Irish source spells St Iberius’s name as Ebur. The euphemism ‘rests in Christ’ using the present tense to indicate ‘died’ also appears to be archaic – it is mirrored in an early Christian funerary inscription from Maastricht that has been dated to the fifth century, the same period as St Iberius of Wexford lived in.

So Hughes was clearly wrong about the entry concerning St Iberius of Wexford. It looks like a contemporary record of his death, not something copied from a much later source. The sixth-century entries in the Welsh annals are pretty much all like this – they preserve evidence of being contemporary records of sixth-century events. The entries that mention Arthur do too, although they are even more difficult to analyse.

Hughes’s suspicions regarding the Arthurian entries in the Welsh annals were misplaced, but other historians have not recognised the key error she made. Most of the scepticism about Arthur relies on Hughes’s analysis – but the sceptics never bothered to ask themselves whether her approach was reliable.

Fifty years later, the situation has changed. There are still books being published that act as if we are still living in the 1970s – as if historical knowledge has not improved since the days that flares were cool. But we now know better. It can now be confidently maintained that the sixth-century entries in the Welsh annals are genuine records of sixth-century events.