Almost fifty years after they were discovered, last month the inscriptions from Uley were finally published in a full academic edition by Oxford University Press. The inscriptions date from the Roman period and most of them are linguistically Latin. But two are not.

Two of the inscriptions from Uley are written in a Celtic dialect, presumably Dobunnic, the language of the ancient inhabitants of Gloucestershire and northern Somerset. The Celtic inscriptions from Uley are the most important linguistic finds from Britain for over a century.

Uley is a small village in the Cotswolds and in the late 1970s an archaeological team excavated the remains of a Romano-British shrine nearby at a site called West Hill. There’s nothing to see there today as the archaeologists covered up the ruins at the end of their dig. The objects they unearthed are all conserved in the British Museum, although the inscriptions have long remained inaccessible. Finally, however, the Uley inscriptions are available publicly and I am allowed now to talk about them.

In Roman times, Uley lay within the Civitas Dobunnorum or the ‘district of the Dobunni’. The Dobunni were a British tribe who had their capital at Cirencester, but their lands appear to have extended south as far as Glastonbury in Somerset. St Patrick seems to have been a member of the Dobunni who was kidnapped by Irish slavers from his grandfather’s villa near Banwell in northern Somerset. Yet the language of the Dobunni had long been thought to be lost, until now.

Among the ruins of the shrine at Uley, the archaeologists discovered the head of a statue of Mercury and many of the inscriptions from Uley record curses addressed to Mercury. But the better-preserved of the two Celtic inscriptions unearthed from the site is addressed to a god called Nodfos. Nodfos appears to be the same Celtic deity who is called Nodens in inscriptions from an ancient shrine excavated in the 1920s at Dwarf’s Hill in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire, on the other side of the River Severn. The linguist who was invited to work on the Lydney finds was J.R.R. Tolkien – and those are pretty big boots to fill.

Tolkien’s contribution to the Lydney Park finds was to offer an analysis of the name of the god Nodens. It’s evident, however, that Tolkien gleaned a lot more than just linguistic knowledge from the Lydney Park excavations. One of the finds from Lydney Park is a curse cast on a thief who had stolen a ring. It is widely thought that Tolkien took the idea of the curse and the ring from Lydney Park and later developed it into the key motif of The Lord of the Rings.

The curse from Lydney Park was published shortly after it was discovered and it reads in translation:

For the god Nodens. Silvianus has lost a ring and has donated one half to Nodens. Among those named Senicianus permit no good health until it is returned to the temple of Nodens

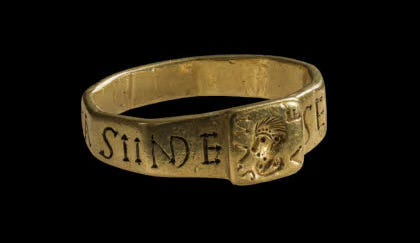

The stolen ring may have been that found in the eighteenth century that is conserved at The Vyne in Hampshire. It is an ancient golden ring with the name Silvianus inscribed into it. It is not clear if Tolkien was inspired by the Vyne ring, but his contribution to the Lydney Park find report makes it clear that he knew about the curse and it has long been suspected that other aspects of the Lydney Park excavations influenced the development of The Lord of the Rings.

But the key linguistic question is whether Nodens and Nodfos are the same figure.

The longer of the Celtic inscriptions from Uley is also evidently a curse and it begins with the following sequence:

ieoroga | tianodfu | osaucuremod

The inscription is written in Roman cursive writing without any gaps occurring between the words. It is 16 lines long in total, but the first few lines seem to form a sentence of a readily recognisable type. The first term is a verb ieoro that is evidently much the same as the Gaulish verb ieuru ‘dedicated’ and gatia appears to be a woman’s name. The inscription begins with the expression ieoro Gatia Nodfu ‘Gatia dedicated to Nodfos’. But who was Nodfos?

Tolkien identified Nodens as a god whose name is derived from a Celtic cognate of the English term need. The Old English ancestor of need is neod ‘desire, longing’ and it seems likely that Nodens was a god of longing. But how did his name become Nodfos at Uley?

The answer can be seen in the medieval Irish equivalent of Nodens. He is Nuadu Airgetlám (Nuadu Silverarm), the king of the Tuatha Dé Danann who lost his arm in combat during the First Battle of Mag Tuired. Nuadu was later killed in battle by the Fomorian leader Balor of the Evil Eye. You couldn’t get any more Tolkienesque than that could you?

Grammatically, Nuadu is a dental stem in Old Irish – it inflects as Nuadat. Nodens is also a dental stem as the name is written with an ending -enti when it is inflected in the Latin phrase devo Nodenti ‘For the god Nodens’. But Nodfos is a vocalic stem, just as Welsh, Cornish and Breton have all lost the grammatical class of dental stems that they must have once had.

That explains why the inflected form of Nodfos ends with -u rather than -enti. But what about the f in Nodfos? The Old Irish form Nuadu indicates that the name of the god had a sound in it that later became an ending -u. This sound is most likely to have been a w. The w has become u in Old Irish, but f in Dobunnic. An earlier w becoming f is a common development in Welsh, Cornish and Breton, and it is not surprising that a similar development seems to have occurred with Nodfos given that Uley is in Gloucestershire.

The longer of the two Uley inscriptions records a dedication to the Dobunnic equivalent of Nodens and Nuadu. It preserves five sentences in total, written in the language of the ancient Britons of Gloucestershire and North Somerset. But the Uley inscriptions are more important than what they actually say. The records of the previously lost language of the Dobunni allow many of the more difficult problems in the early history of southwestern Britain to now be resolved and these have a particular importance for understandings of the Arthurian period.

Thanks for supporting the Age of Arthur this year — and Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to everyone!

This linguistic analysis is so fascinating - thank you for sharing this!