Writing in the twelfth century, Geoffrey of Monmouth claimed that King Arthur’s sister Anna was married to King Loth of Lothian and that he made Loth’s brother Urianus the king of Moray. The tradition seems rather strange at first – could a sixth-century British king really decide who was to rule over the Picts of Moray? Urianus’s kingship of Moray may be an invention of Geoffrey’s with no historical basis to it. But the names recorded for the rulers of Pictland in medieval sources suggest that the kings of the Picts were often Brittonic-speakers, as if they originally came from further south. Their names suggest that early medieval Pictland was ruled by a Celtic-speaking elite, not kings of Pictish descent.

How the Picts came to be ruled by kings with Brittonic names is not entirely clear, but evidence of a Celtic elite seems to be revealed in some of the Pictish inscriptions. While the language recorded in the Pictish inscriptions does not seem to be grammatically Celtic, names that appear to preserve characteristically Brittonic linguistic features are sometimes found preserved in them. A particularly difficult, although revealing example is recorded on a stone from Newton House that has long been recognised to record inscriptions in two different alphabets.

Discovered in 1803 in a nearby fir plantation, the Newton stone is conserved today in the grounds of an old laird’s mansion near Insch in Aberdeenshire. The stone preserves two inscriptions: one in ogham, the other in a form of Late Roman Cursive. The Newton stone is of blue gneiss, it is over two metres tall, and two Pictish symbols are preserved on it: a mirror symbol and a spiral. The Old Roman Cursive used on the Newton stone appears to date its inscriptions to the Arthurian period – about the sixth century. But the use of two different writing systems is not the only striking feature of the inscriptions on the Newton stone.

Medievalists have long been able to read ogham inscriptions. The medieval Irish recorded everything they knew about writing, including about their own alphabet ogham. Medieval Irish tracts explain which ogham letters have which sound values. That makes reading Pictish inscriptions written in ogham a fairly simple matter. It’s what the words they record mean that is the problem.

The other inscription on the Newton stone has long been harder to make any sense of because the cursive letters it records often seem a bit strange. But most of the ogham inscription on the Newton stone is simple enough to read. It is written vertically, it reads from top to bottom, and it begins with a name Iddarrnnn followed by a second name Vorrenn. Iddarrnnn appears to reflect a Brittonic form of the Roman name Æternus, much as the Cumbric name Padarn reflects the Roman name Paternus, and Vorrenn may be a cognate of the Breton name Vuorin. The two names are then followed by several unclear letters whose analysis is less clear.

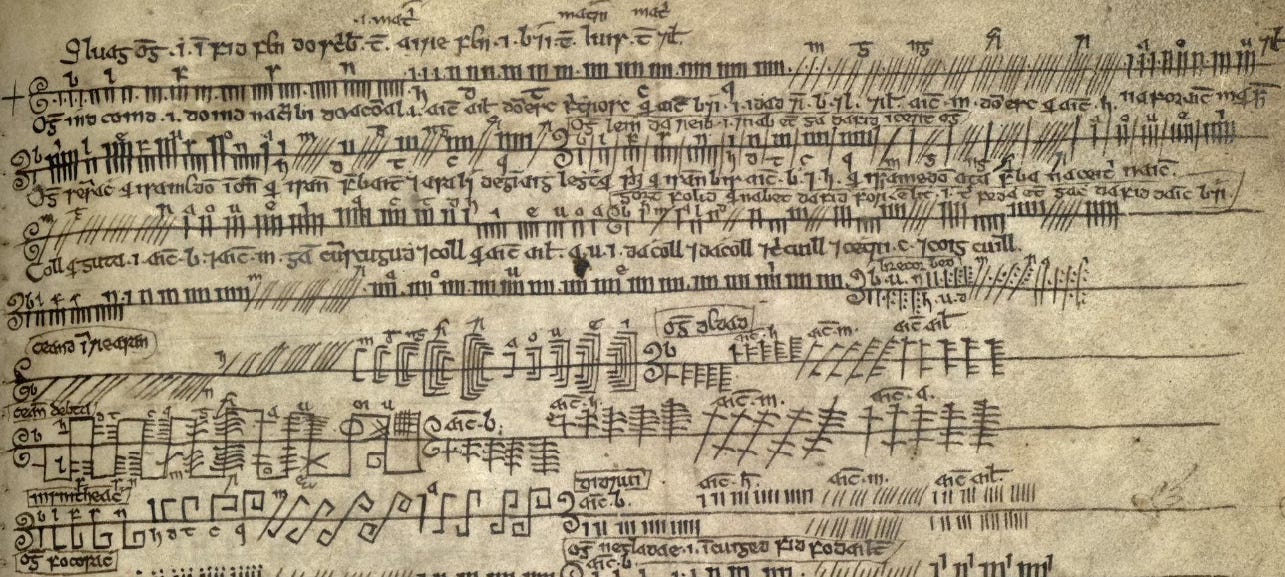

How to make sense of the cursive inscription on the Newton stone has long been more controversial. The Romans used two different forms of writing – capitals and cursive – and most Roman inscriptions are written with capital letters and are simple enough to read. But Roman cursive, like most early forms of handwriting, is usually much more difficult to make out, and the cursive inscription on the Newton stone, written in several distinct lines running horizontally across the stone, is particularly difficult.

The first three lines of the cursive inscription on the Newton stone have most recently been read as ette | eurermeq | geonouotθ, with the second line finishing much further around to the right of the stone than the first and third ones. The final character on the third line has an unexpected form, comparable to the Greek letter theta, and most of the rest of the inscription appears to be illegible.

It has long been obvious that the cursive inscription on the Newton Stone begins with the sequence ette that is recorded in several other Pictish inscriptions and it seems to mean ‘(memorial) stone’. The inscription on the Lunnasting stone begins ettecuhetts ‘Cuhett’s stone’ and a more fragmentary inscription from Cunningsburgh begins simply etteco- with the text then breaking off, as if it meant ‘C’s stone’.

The following line on the Newton stone begins with a sequence eurer followed by meq. This is best understood to be a name Eurer followed by the filiation marker meq ‘son’ also employed in Scottish Gaelic and Irish names where it is usually written mac or maic. The name of Eurer’s father is evidently also preserved in the third line’s sequence geonouotθ.

The most remarkable aspect of the third line is the name that comes after meq. It seems to be the Pictish name Geon recorded by St Adomnán in his Life of St Columba. In a Scottish Gaelic inscription, Geon would be expected to be inflected in the genitive case when it came after a filiation marker in order to indicate ‘son of Geon’. A similar name Geno that is recorded in an entry for AD 588 in the Annals of Ulster is inflected as a u-stem, and the corresponding inflection recorded on the Newton stone appears to be ‑ou, as if Geon is also a u-stem.

The most interesting thing about the name Geon is what it has been taken to mean. St Adomnán mentions it as a description of a cohort of warriors led by Artbranan, a Pict who came to Iona to be baptised by St Columba. Geon has generally been taken to be the name of a person, but it has also been associated with the name of the Pictish territory of Cé. Cé was located in Aberdeenshire and its name appears to be preserved in the name of Bennachie, a range of hills in Aberdeenshire whose name means ‘peak of Cé’ in Gaelic.

It is not clear that Artbranan’s cohort came from Cé, however, or that Geon and Cé reflect the same name. The Geno mentioned in the Annals of Ulster was a man whose grandsons died in 588 and nothing else is known about him. But finding the name of Cé on a Pictish stone from Aberdeenshire would make sense if the name Geon meant ‘person from Cé’. The form Geon recorded by St Adomnán has been taken to be an adjective and personal names were often derived from place-names in such a manner.

So who were Iddarrnnn Vorrenn and Eurer meq Genou? What was their relationship to each other? The inscriptions on the Newton stone do not make it immediately clear, although the use of two different writing systems suggests what may have occurred. Roman cursive was not employed for funerary memorials, but ogham certainly was. Iddarrnnn seems to have been the name of the person the stone was set up to commemorate and Eurer the commissioner or creator of the memorial.

Iddarrnnn also appears to have a Brittonic name, unlike Eurer who seems to have been the son of a local man from Cé. The inscriptions on the Newton stone appear to preserve evidence for a man whose name is written in a distinctively Brittonic manner having a memorial stone made for him by a local Pict – as if Iddarrnnn was a foreign-born lord and Eurer a local craftsman.

By the sixth century, it appears that a Celtic-speaking elite had settled in Pictland. The Pictish language continued to be recorded on memorial stones, but most of the names of the rulers of the Picts recorded in later sources seem to be linguistically Brittonic. The Brittonic elite lost power in the ninth century, however, when Gaelic-speaking kings came to rule over Pictland. In the time of Kenneth MacAlpin, the Brittonic-speaking elite of Pictland was replaced by Gaelic speakers, and Scottish Gaelic would eventually become the language of most people in Moray and Aberdeenshire.

What do think the Pictish "Drosten" has any relation to the Old High German "Trosten"?

Absolutely fascinating! Thank you!