The most mysterious people in Britain during the Arthurian period are the Picts. They are first mentioned in Roman accounts and several different figures associated with Arthur in the medieval romances were considered Picts. But who the Picts were has long been controversial – unless you live in Scotland.

In Scotland, the Picts are Celts, or that’s what we are told. But linguists have never agreed with the assertion. A key principle employed by linguists is Occam’s razor or explanatory parsimony. The explanation that requires the least assumptions is the most likely one to be correct. A failure to follow this basic rule bedevils all the attempts to prove that the Picts were Celts. It’s quite obvious what the problem is when you view it from the perspective of Occam’s razor.

In the nineteenth century, Scottish patriots seemed to be at a disadvantage to the Irish and the Welsh. In an attempt to assert their cultural distinctiveness – to show how very different they were from the English that is – Irish and Welsh intellectuals stressed their countries’ Celtic pasts. The English may have had all the guns and ships and the country mansions. But the Irish and Welsh were Celts. The intellectual movement blossomed into a wider cultural phenomenon called the Celtic Revival. The Scots were a bit late to get in on the act, but there was a key problem.

In order to be proper Celts, many Scots also felt the need to not be Irish. The Irish revival was Catholic and Scottish patriots wanted none of that. What was the point of those Orange marches every year in places like Glasgow? Chairs in Celtic Studies began to be founded at all the universities in the Celtic countries, but Gaelic was an immigrant dialect, brought across the North Channel by Irish migrants at the end of the Roman period. The truest Scots were the Picts, the ancient enemies of the Romans. But who were the Picts exactly?

Alexander Macbain thought he knew. The Swiss linguist Rudolf Thurneysen, a recognised master of the field, had explained the place-names in Scotland that began with Pit- as Celtic coinages. Not like Irish and Gaelic that had no native words that began with p-, but rather more like Welsh. There was even a Welsh word peth ‘thing’ and a Latin word petia ‘piece’ that was used in medieval land titles to mean ‘piece of land’. The place-names beginning with Pit- were extremely common: Pitlochie, Pitcarlie, Pitgrudy, Pitfichie, Pitacree and Pitairlie. They are everywhere in northern Scotland. They must have been the names of Pictish landholdings and Pictish must accordingly have been a p-Celtic language, closer to Welsh than to Irish.

Macbain rushed off a long article on the matter for the Celtic Review. He’d become the editor of the Scottish literary magazine that all the key people in the Scottish wing of the Celtic Revival read. A Gaelic-speaker from Inverness, right in the centre of Pictland, Macbain was sure he was right and he managed to convince a lot of other people that he’d figured it out. He published his proof in 1887, but was he right?

The first question to ask is if the Pit- names preserve a p-Celtic root or just a Latin loanword. Which one would you choose? Macbain’s etymology requires there to have been a p-Celtic word in Pictish related to Welsh peth ‘thing’, but it has to have been used with the meaning of medieval Latin petia ‘piece (of land)’. Which derivation is simpler? For the Pit- names to be p-Celtic, you would have to assume that medieval Latin petia was loaned from a Celtic language and that Pictish, unlike Welsh, had kept the meaning inherited by Latin. Which derivation is simpler, p-Celtic or Latin?

The only reason that you’d accept the much more complicated Celtic explanation would be if you were rather desperate for the Picts to have been Celts – either because, like Macbain, you wanted Scotland to have its own Celtic tradition separate from that of Ireland, or you think that theories proposed by Scottish nationalists well over a century ago have a numinous quality to them. The idea that the Pit- names are evidence that the Picts spoke a p-Celtic language is far-fetched. But the story just gets worse.

In 1892, the Welsh Celticist Sir John Rhys, the first Professor of Celtic at Oxford, published his analysis of the Pictish inscriptions. Macbain had never considered them – he found them incomprehensible. They are written in ogham, a tally-like writing system first employed by the Irish, and Rhys contended that the idea that the Pictish inscriptions recorded a Celtic language was ridiculous: “Let them explain it as Welsh, and I shall have to confess that I have never rightly understood a single word of my mother tongue.” Macbain responded abusively, calling Rhys’s analysis of the inscriptions lunacy. But unless the Pictish inscriptions were linguistically p-Celtic, what value could there be in Macbain’s place-name studies?

Macbain continued to scour Scotland for place-names he thought could be explained as p-Celtic or Welsh. But most Celticists agreed with Rhys – the Pictish inscriptions could not be explained as Celtic. That remained the consensus view until the 1990s when something new started to occur in Scottish academic circles.

After the establishment of the devolved Scottish Parliament, a new generation of medievalists who really wanted the Picts to be Celts gained the ascendency in Scotland. Rather than hurling abuse at critics who agreed with Rhys, the new game was to pretend that the Pictish inscriptions were just too difficult to understand to be used as evidence. Place-names were cool again. Road-signs were all being changed to include the Gaelic names of places, many of which had to be dug up out of very old books. Lots of money was now to be had to study Scottish place-names, even if the Pictish inscriptions remained interminably cranky.

It should not surprise anyone to discover that the Picts are now undisputedly Celts again in Scotland, more Scottish than any bagpipe or sporran. Every Scottish book published on the Picts agrees, without qualification. It’s a pity that those damn inscriptions are so odd, but all those people who still think that Pictish was not a Celtic dialect must be wrong.

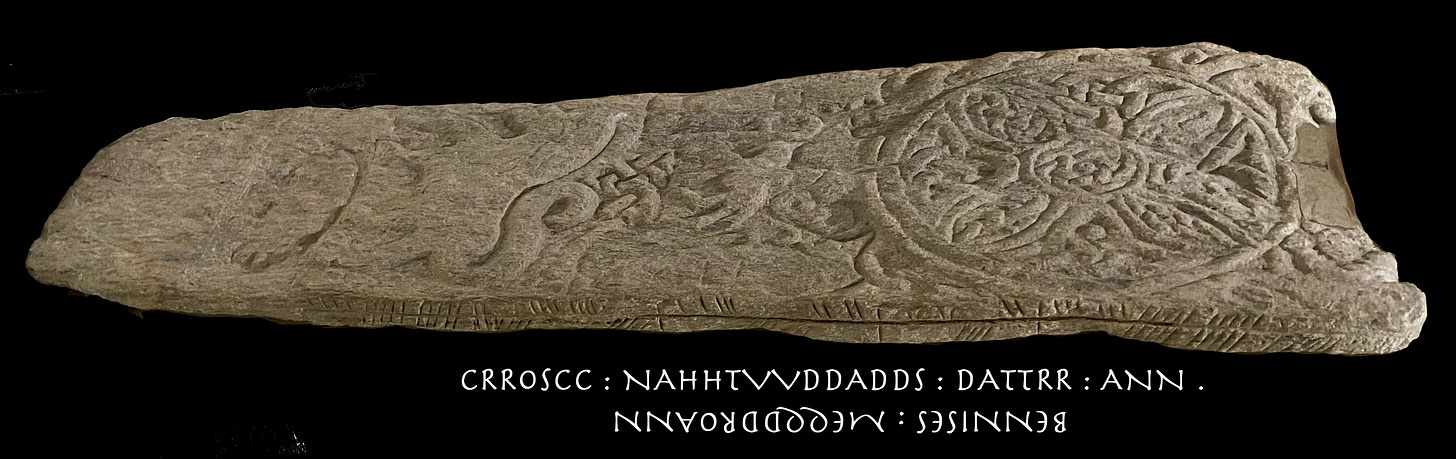

The main problem with this new consensus is that the Pictish inscriptions can be made sense of as long as you assume that they are not written in a Celtic language. They clearly feature names suffixed by -s in the manner of an English apostrophe s (’s). One of the inscriptions, from Bressay in Shetland, begins with what Rhys read as ‘the cross of Nahhtvvddadd’ with the name of Nahhtvvddadd suffixed by an -s. But Irish, Gaelic and Welsh don’t have an equivalent to an English apostrophe s and Nahhtvvddadd doesn’t appear to be a Celtic name. There are ten or so names suffixed in this manner preserved in the 30 odd extant Pictish inscriptions and it is a clear sign that the inscriptions are not written in a language related to Welsh.

The linguistic evidence points to Pictish being a language from a different branch of Indo-European than Welsh. English is distantly related to Welsh and Irish as all three are languages from the wider Indo-European family. The suffixation with -s is most simply explained as being a marker similar to English apostrophe s that was lost from the Celtic languages. It is retained not just in English, but also in the Baltic languages, Hittite and ancient Indic. Most of the Pictish inscriptions can be made sense of fairly readily once you make this jump – Pictish is an Indo-European, but not a Celtic language. It’s the Occam’s razor solution and it allows the Pictish inscriptions to now be understood. Unless you are a Celtic Studies professor in Scotland of course where Pictish is Celtic because it always has been. Macbain told us that.

"caste, Nechtan's daughter and Lord of Dyfed"

Brenin being a word for a Welsh King or lord, the language seems related to Old High German. The sentence seem implied a marriage between a Pict Princess and a Welsh prince or king, then again they could be using "Brenin" as a loan word.

About the Pit- placenames, all formed with a Gaelic descriptor. I take the issues you describe. But, I think that words are a bit more fluid in their usage and their 'fads', so I'd have no problems thinking this is an inherited word similar to the Welsh peth, but which has slightly slid in semantic scope and specific application in Pictland. The other thing that is unexplored about the pit- names is that they may reflect some sort of relationship to the churches, and possibly pagan nemetons before them, so the pit- could have a fairly specific application in Pictland that it didn't get elsewhere.