“And what should they know of England who only England know?” is a famous line from a poem by Rudyard Kipling. Born in British India, Kipling was criticising nationalists who had never travelled outside England. But the same criticism might be made of those who ignore the history of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes before they migrated to Britain.

The histories of the peoples who came to Britain during the fifth century are relatively clear, but most of the literature about how they lived before they migrated is written in Danish and German. Every year conferences are held where the early history of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes is discussed. The findings presented at these symposia, however, are often ignored by British researchers. It is common to find that British archaeologists know next to nothing about what was happening in the homelands of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes in the fourth and fifth centuries. Their historical blindness is often quite extraordinary.

One of the best excavated pre-migration settlements of the Saxons is Feddersen Wierde, on the north-western coast of Germany. The Feddersen Wierde site was excavated from 1955-1963, and at its peak in the third century, the settlement featured 26 longhouses and had a population of about 300 people. The early Saxon village was abandoned in the fifth century and it is quite clear why. The whole population seem to have gotten into their boats and migrated elsewhere.

The Feddersen Wierde excavations were long ignored by the British archaeologists who argued that the scale of the Anglo-Saxon migrations had been vastly overstated. But German archaeologists knew better – settlement after settlement on the North Sea coast emptied in the fifth century. The Anglo-Saxon migrations are so well documented, it was clear that the British archaeologists who tried to downplay their scale and nature did not know what the evidence from Germany indicates.

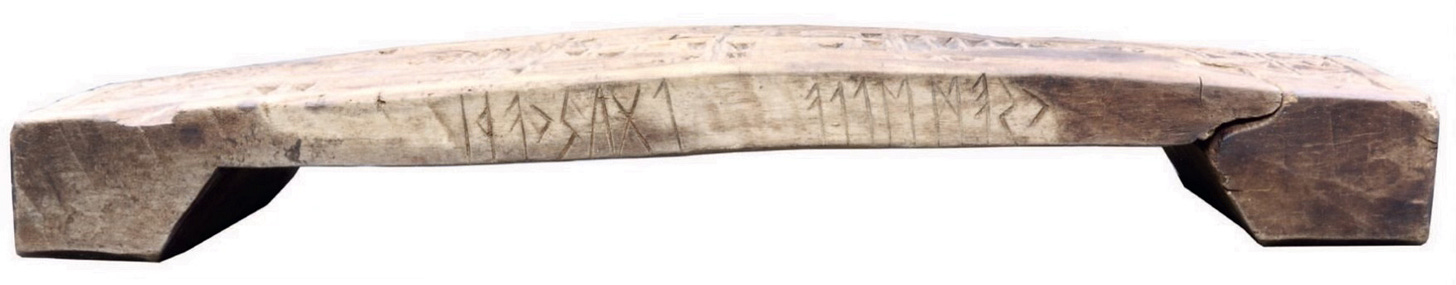

In 1994, German archaeologists also excavated a graveyard near the early Saxon settlement of Fallward, not far from Feddersen Wierde. In it they discovered the grave of a chief and they could tell from tree-ring analysis of the timbers that were used for his coffin that he had been buried in AD 421 or shortly afterwards. The chief’s coffin was shaped like a boat and he had been buried along with his wooden throne. On the footstool of the throne, a runic inscription was preserved that can be read quite easily.

The inscription on the Fallward footstool runs from right to left. It begins with the word ksamella which seems to be a slightly irregular, but very early form of Old English scamol ‘stool’. The description of the footstool is followed by runes which read lguskaþi. It seems very likely that this sequence was supposed to be read as Alguskathi, with the a-rune from the end of ksamella meant to be read twice. Alguskathi literally means ‘elk-scather’ and the back of the stool features a carving of a dog biting a deer as if it were a pictorial representation of Alguskathi’s name .

Alguskathi was also found buried with a belt. But it isn’t a Saxon belt – it is one of a type commonly found in the graves of Roman soldiers. Alguskathi seems to have formerly served as a soldier in the late Roman army. St Gildas records in his Ruin of Britain that the Saxons had first been invited over by the Britons to help protect them from Pictish and Scottish raiders, and Alguskathi is exactly the kind of chief who might have been invited to come to Britain at the time.

It is also quite clear what Alguskathi’s people did next. They buried Alguskathi, just as the poem Beowulf describes the Danish king Scyld’s people cremating his remains in a boat. Sometime soon after, the Saxons of Fallward got into their boats and migrated somewhere else. But where did they end up? It seems likely that they settled in Essex or Sussex as the kingdoms of the East Saxons and the South Saxons are nearest to Fallward. But Saxon settlements are also known from the north coast of Belgium and France. Not all of the peoples who migrated from the northwest coast of Germany during the fifth century ended up in England. It’s likely, however, that the majority of the Saxon migrants at the time headed for Britain.

Analysis of the DNA extracted from bones found in early graves from the southeast of England have shown that up to three-quarters of the sixth- and seventh-century population were descended from immigrants from Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and France. Many of the local British population must have been enslaved, massacred or fled, just as St Gildas records in his Ruin of Britain.

One of the clearest records of the migration is the appearance of runic inscriptions both in graves like that of Alguskathi and from fifth- and sixth-century Britain. The oldest runic inscription from Britain was discovered in the 1930s in a grave near Caistor St Edmund in East Anglia. It is inscribed on a bone gaming piece and it describes what kind of bone the piece is made from: raïhan ‘from a deer’.

The oldest clearly Saxon find, however, was discovered in the 1980s near Watchfield in Oxfordshire. It was found in the grave of a young man dated to the middle of the sixth century and it is engraved on a metal fitting of a purse in which a set of scales had also survived. The scales include weights that show that they were used to weigh silver bullion. The weights allowed the user to determine how much an amount of hacksilver was worth in Frankish tremisses, small golden coins first issued in the late fourth century. The coins are called þrymsas in later Old English sources and they were the main unit of currency used in the sixth century.

The runic inscription on the Watchfield purse reads haribokiwusa. The first term, hariboki, means ‘of the army-book’ and it seems to indicate that the scales were used to calculate the wages of Saxon warriors. The Roman army was highly bureaucratic and even ancient pay receipts of soldiers have survived. St Gildas’s description of the original arrangement made between the Britons and the Saxon migrants indicates that it was probably a formal written treaty that stipulated how much the Saxons would be paid to protect the British, and the Watchfield purse suggests that similar calculations were still being made in the sixth century.

The second term recorded on the purse fitting is an Anglo-Saxon name Wusa and it seems likely to be that of the young man buried in the grave. The first term appears to describe what was carried in the purse – a military paybook that has now rotted away, along with a set of metal scales – and the second term records who had responsibility for keeping it.

Very good point re the lack of a European view of the period and not just British-centric one. Of course, the Western Roman Empire had the same Euro-centric view such that the English Channel was a waterway conduit not a barrier. A view brought into sharp relief by the Carausian rebellion and the short lived Gallic Empire before it.

Re the indigenous population of the SE, it is worth remembering that when the economic system in Britain collapsed, it is possible that many of the inhabitants simply went 'back' to Roman Gaul (or other Roman territories). There are many attested hoard burials around the turn of the 5th century in the SE and 'villa' belt of Romanised Britain. This could be taken to infer that the owners were worried about Imperial tax collectors appropriating their wealth when they moved back into areas under Imperial control. Maybe...

Of course there is also the possibility of westward migration from the SE areas but this may come later. My personal opinion is that denuded of a good chunk of the population allowed unsanctioned immigration in the SE in a patchwork process rather than an 'invasion' style event. This would corroborate the admittedly sparce data from burials that show battle wounds on 5th century bones are remarkably low. Using the 'perfusion' model allows a build up of immigrants from the Northern areas of Europe which eventually ended in nascent kingdoms forming relatively late.

Great article and would love to see more.

Good article. Important to compare the British archaeology with what was happening on the Continent.

"Many of the local British population must have been enslaved, massacred or fled, just as St Gildas records in his Ruin of Britain." I'm not wholly sure this is what the genetics shows, nor do we know if this is what Gildas refers to in his lament about the destruction of British cities. He also thought Hadrian's Wall was built in the fifth century, so his understanding of the wars, rebellions, and invasions before his birth can easily be read as hyperbolic extrapolations of what really happened. It was in his interest to show the Saxons as savage heathens, and the Christian kings who trusted them as backsliders. No doubt Saxons invaded and subjugated local populations along the south coasts, but this would have been significantly variable by region. Most of the Saxon expansionism comes from later, such as the emergence of Wessex in the mid-sixth century.

You may be aquainted with it, but the Gretzinger et al 2022 archaeo-genetics paper is very illuminating on the fate of local populations in the period. It and other papers also point to a much more extended period of cross-colonisation from Gaul and Germanic homelands.