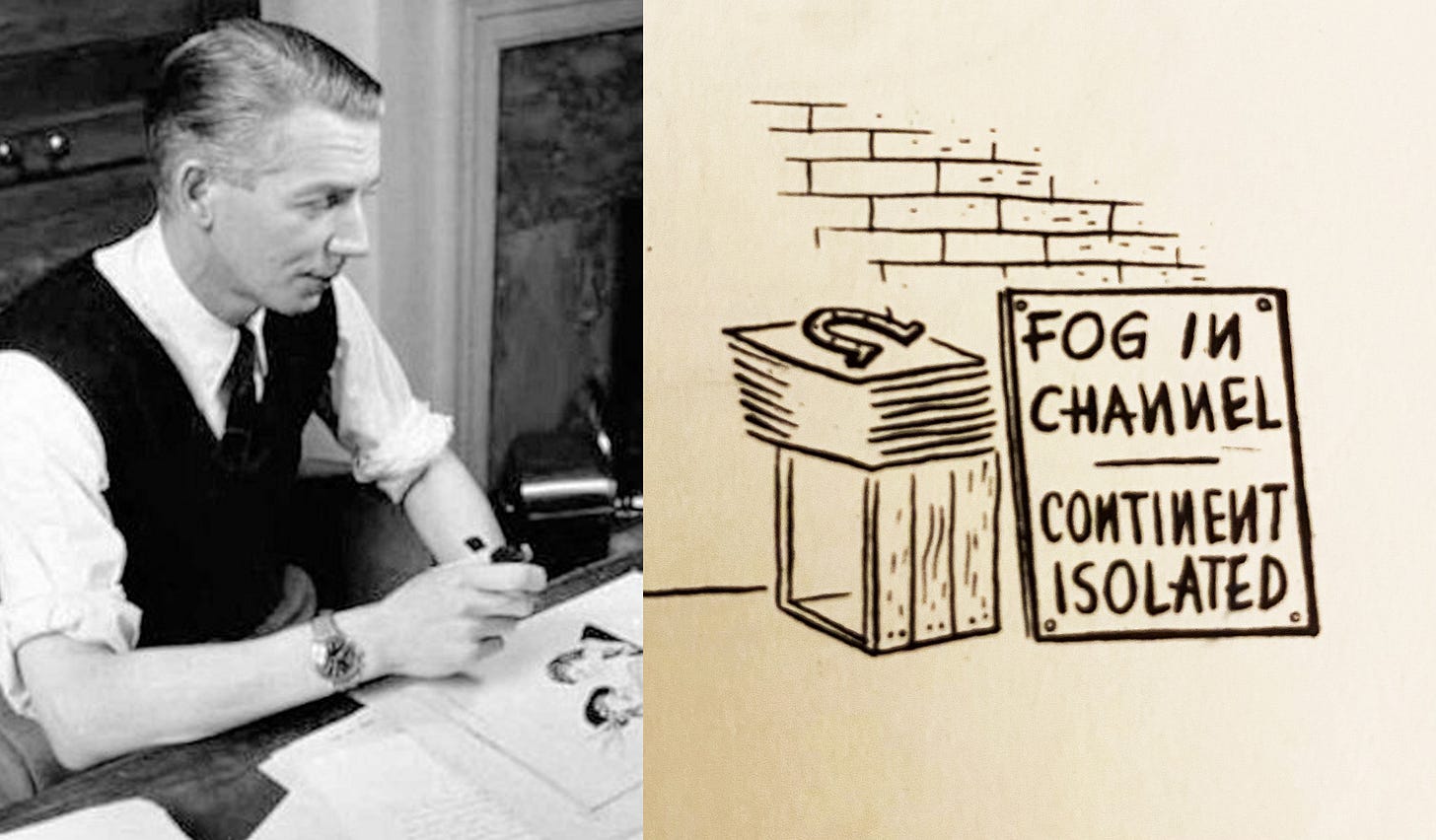

Most people in the UK will know about the mock headline “Fog in Channel: Continent Isolated”. It was invented by the Canadian cartoonist Russell Brockbank in the 1930s. It’s a quip that criticises English isolationism and it was often bandied about during the debates over Brexit. What is less well recognised is that the same attitude has long prevailed among English historians, even if they now may use the description “British’” rather than “English”.

Most people would also know that the description English has something to do with the Angles, one of the three peoples mentioned by St Bede as invading Britain in the fifth century. But English history books don’t ever say much about where the Angles came from. It is as if English history only began when the Angles landed in Britain.

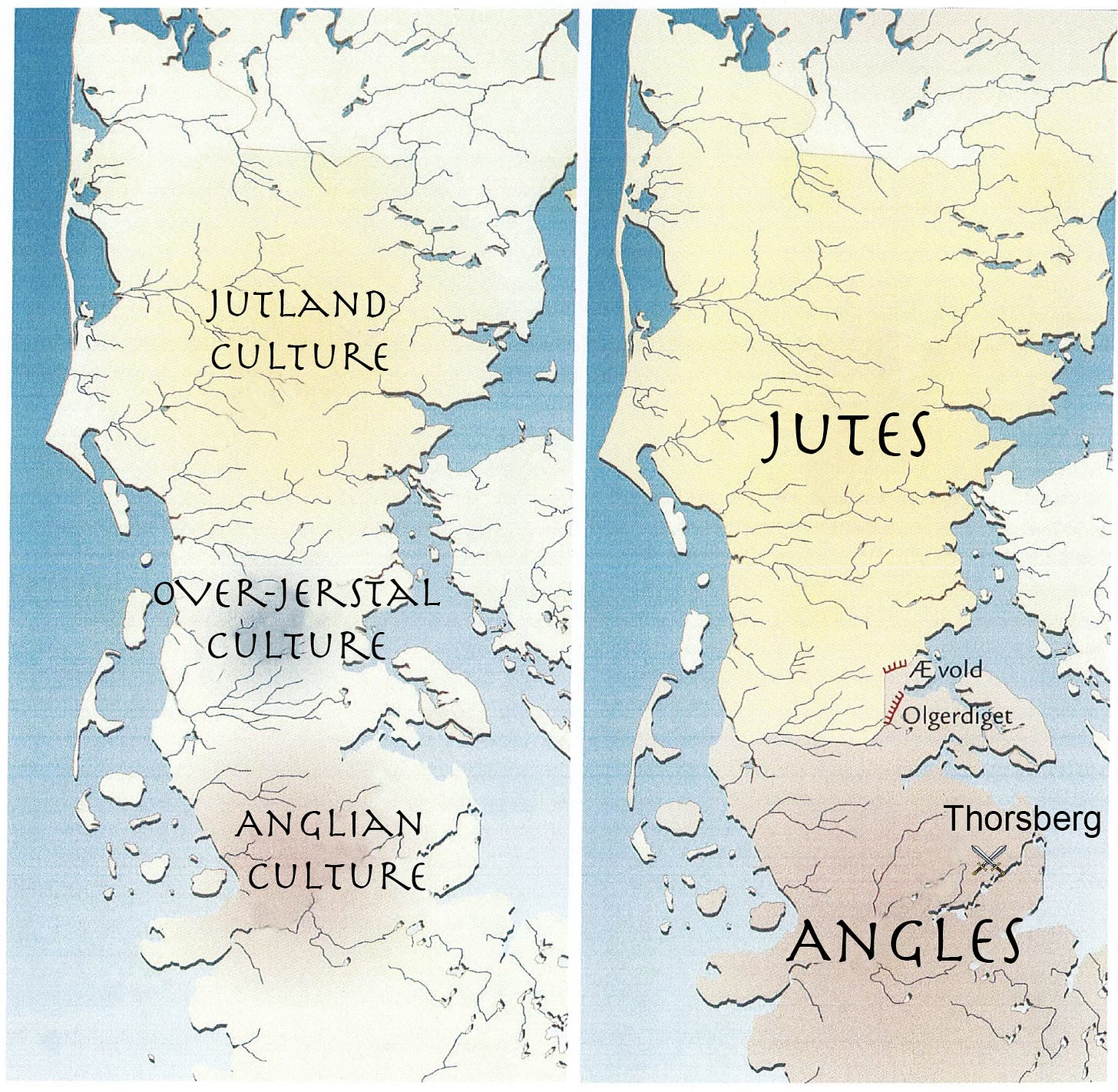

The Angles came from what is now called Angeln, a peninsula in northern Germany. St Bede was well aware that the Angles came from Angeln – in his Ecclesiastical History he calls the peninsula Angulus desertus ‘deserted Angul’. Angeln appears to have suffered a significant population decline during the fifth century, so St Bede seems to have had his facts right. But why don’t English history books start with an account of Angeln?

David Hume’s History of England was the most popular history book in Britain during the nineteenth century. Hume was a Scotsman which annoyed English historians, but Hume began his account with the Roman invasions of Britain and stepped over the Anglo-Saxon period as quickly as he could. His book praises the rise of democracy in England and the development of parliamentary government. He wasn’t really interested in the English at all, only the origins of the British political system.

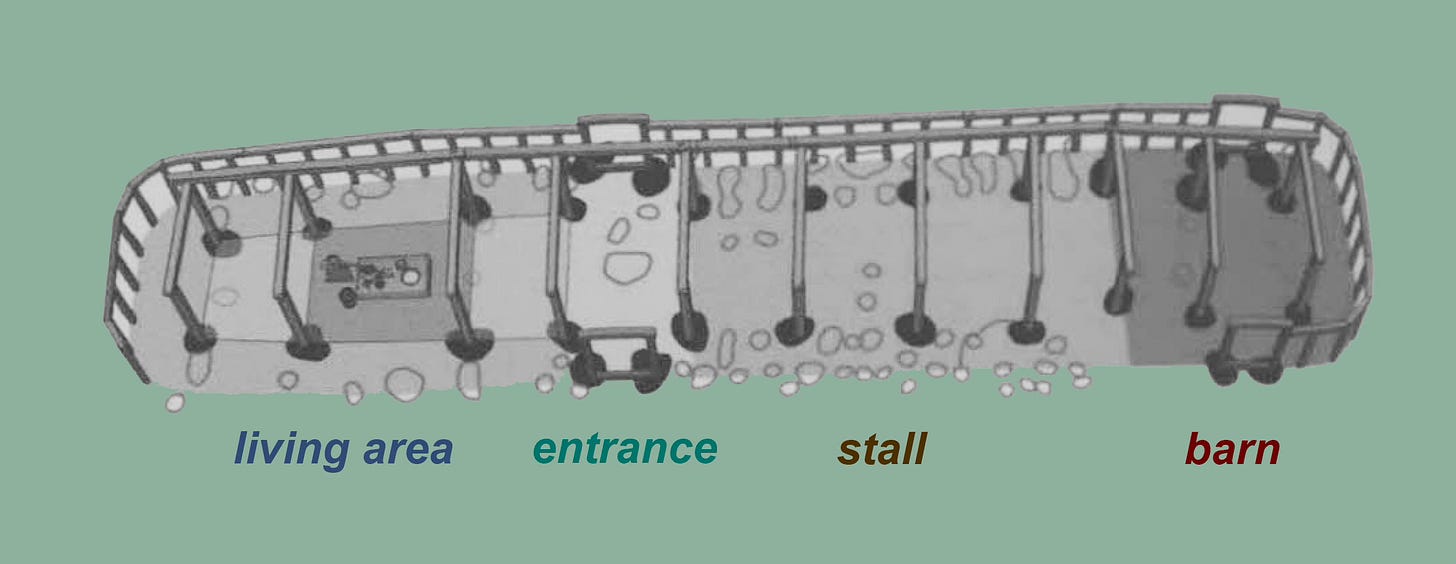

German and Danish archaeologists have long told a different story. Archaeologists in Germany and Denmark connect the Angles with characteristic ancient finds that go back to the time of the Roman invasions of Britain. The area of early Anglian settlement is typified especially by a longhouse of a peculiar design and dykes that were built to defend Angeln from the Jutes during the early Roman period.

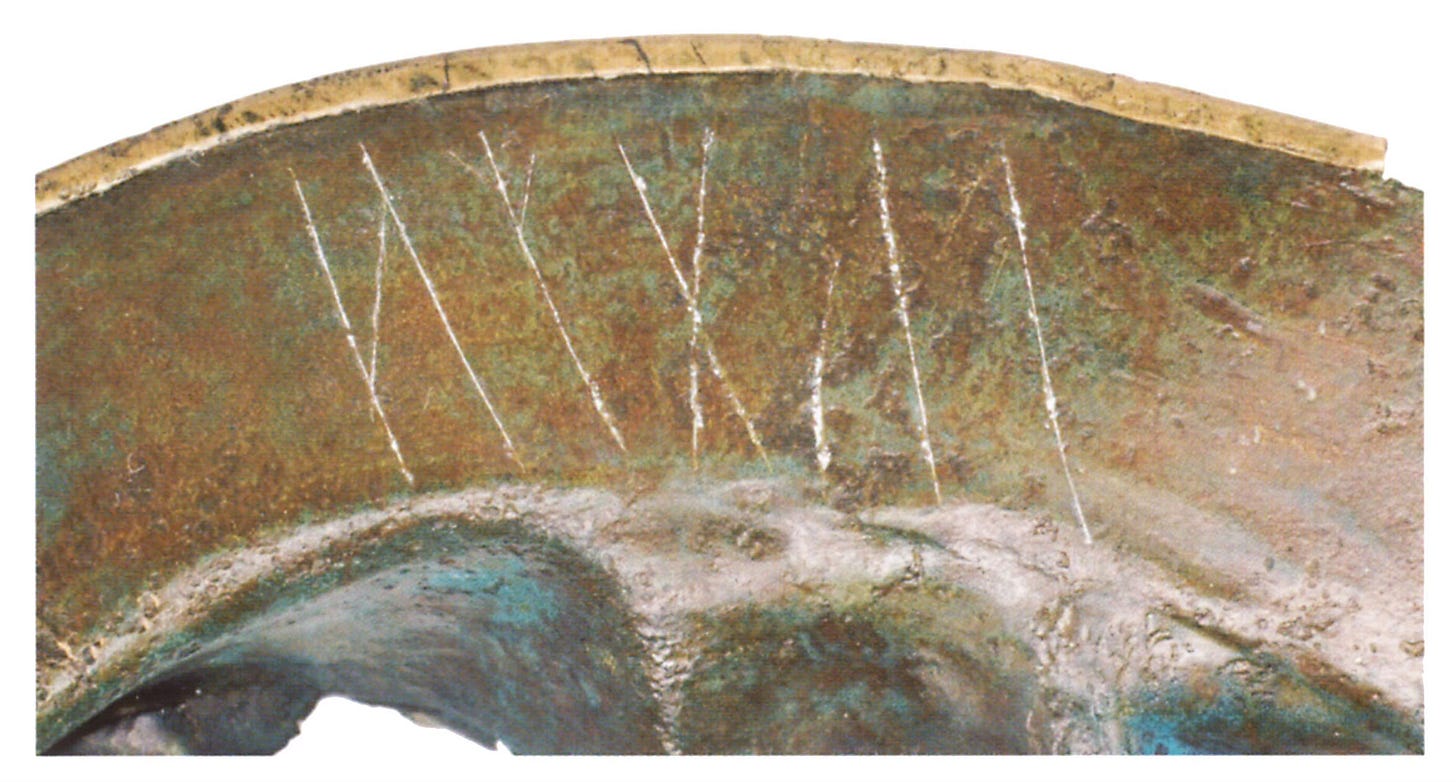

Early inscriptions are also known from the area. In the late nineteenth century, Danish archaeologists dug up a large find of ancient weapons from a duck pond at Thorsberg in Angeln. Angeln was governed by the King of Denmark at the time of the excavations and the region was only finally ceded to Germany at the end of the First World War. The Thorsberg finds included two runic inscriptions, the oldest one inscribed into the back of the boss of a shield.

The bronze shield boss was deposited in the duck pond at the beginning of the third century and its characters can be read quite simply. Under magnification, it is clear that the inscription, written from right to left, reads ansgzh.

The last character in the inscription is widely accepted to be an abbreviation, probably for the verb haite ‘I am called’, and the rest of the runes preserve a name. But who was Ansgz? Why did he write his name of the back of the Thorsberg shield boss?

The name Ansgz is much the same as Anschis, a figure recorded in an early medieval geography known as the Ravenna Cosmography:

there is an island called Britain in the west ocean where the Saxons, coming from Old Saxony with their leader Anschis, now live.

Anschis is clearly the figure that St Bede calls Oisc, the founder of the dynasty that ruled Kent in early Anglo-Saxon times. His name was later affected by the same sound changes that distinguish German and Dutch gans ‘goose’ from English goose.

Ansgz lived two centuries before the early Kentish king Anschis. But it is surely no coincidence that both men had the same name. They must have spoken much the same language and come from similar cultural backgrounds.

Archaeologists also now think they know why all the weapons and armour were thrown into the pond at Thorsberg. It was part of a religious ritual alluded to in Roman accounts such as those of Tacitus:

[they] had devoted, in the event of victory, the enemy’s army to Mars and to Mercury, a vow which consigns horses, men, everything indeed on the vanquished side to destruction.

The Thorsberg finds appear to have belonged to an army that had invaded Angeln and been defeated. The Angles subsequently sacrificed the weapons and armour they captured to the gods of war. Archaeologists don’t know what happened to the defeated invaders, but their fate is assumed to have been gruesome.

The invading army seems to have come from further south which should mean that Ansgz was a Saxon. He probably wrote his name on the back of the shield boss because he was a weapon smith and recorded it as a hallmark – much like the LV logo found on Louis Vuitton handbags today.

It seems quite ridiculous that English history books do not start at Thorsberg and with other early archaeological finds from Angeln. But it should be obvious to most people why they don’t. The Oxford History of England, established in the 1930s to replace Hume’s more famous account, was supposed to be a celebration of Englishness – and its authors wanted to celebrate the Roman past of Britain as much as, or more than, the legacy of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes.

The authors of more recent works such as the Cambridge History of Britain have less excuse. But it is difficult to get historians to change their minds. In the opinion of English historians, England begins, not with the Angles, but instead with the Celts and the Romans. That’s not quite how the Welsh see it of course – and neither should English historians.

Churchill's "A History of the English-speaking Peoples" is a good start

Wellcome Trust / Oxford University research:

“The majority of eastern, central and southern England is made up of a single, relatively homogeneous, genetic group with a significant DNA contribution from Anglo-Saxon migrations (10-40% of total ancestry). This settles a historical controversy in showing that the Anglo-Saxons intermarried with, rather than replaced, the existing populations.”