A memorial stone near Ramsgate records the 1500th anniversary of the landing of the Jutes in Kent. It was paid for in 1949 by the King of Denmark, and the replica ship Hugin that was used as part of the commemorations can still be visited nearby. Four years earlier, Britain had freed Denmark from German occupation, but in Denmark Hengist and Horsa were held to be speakers of an early Norse or Danish dialect, not an ancient form of English.

In the 1950s, however, Danish archaeologists made a significant discovery of weapons in a lake in the Illerup valley in Jutland. Thousands of weapons, arms and other accoutrements dating from the early third century were uncovered from the site, several of which were engraved with runic inscriptions. Over 15,000 pieces of Iron Age military gear have been recovered by archaeologists from Illerup, including the remains of swords, sheaths, sword fittings, belts, spears, shields, shield bosses, shield mounts, axes, bows and arrows, coins and equestrian equipment. They were deposited to honour the gods of war as part of a religious ritual common in Scandinavia at the time.

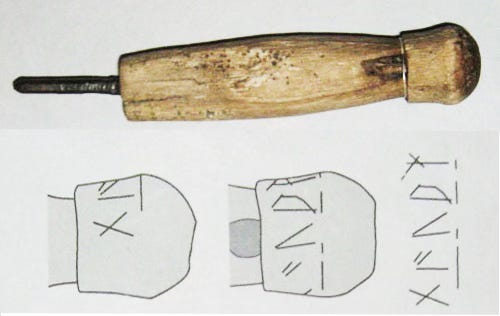

Two of the spearheads found at Illerup have the name Wagnijo engraved or stamped into their blades in runes, and one of the shield handles records that it was made by another craftsman called Niþijo. Other names including Swarta and Laguþewa are recorded on objects excavated from the site, but the most interesting inscription from a linguistic perspective is that preserved on the handle of a fire steel. Fire steels are the tools that were used to start fires at the time (before the invention of matches) and the fire steel from Illerup has a single runic sequence gauþz preserved on it. The Danish expert who published the find thought that the sequence spelled out a name, but gauþz would be a very odd name if the form were early Danish.

The main linguistic problem with the Illerup sequence gauþz is that it does not make any sense from a Danish or Old Norse perspective. Yet the sequence is perfectly understandable as a linguistic form ancestral to English. An Old English verb geunnan ‘to grant’ is recorded and it has past tense forms such as geuþe ‘granted’. The term on the Illerup fire steel preserves the expected form of an early past participle of Old English geunnan ‘to grant’ and it seems to indicate that the fire steel was something that had been granted – in other words, the inscription indicates that the fire steel was a gift. The weapons found at Illerup had all been sacrificed to the gods and it appears that the fire steel was engraved at the time with a runic inscription that indicates that it had similarly been given to the gods.

But were the people who deposited the finds from Illerup Jutes? Roman accounts only mention a people called the Eudoses in central Jutland, which is evidently a different form than Jute. The name of the Jutes appears to be spelled as Eucii by the Frankish King Theudebert in a letter to the Byzantine Emperor and t is often written as c in medieval Latin when it comes before an i. Eucii might also be expected to develop later to Iuti ‘Jutes’ with the diphthong eu developing to iu and loss of the final i. But Eudoses and Eucii seem to be different forms – so what has happened?

It makes sense that Jutland was named after the Jutes, but Danish linguists have never been sure how the Jutes received their name. The spelling Eudoses is recorded only once, in the Germania of the Roman historian Tacitus, and it may be that it has only survived in a slightly corrupted form. It is quite common for early Germanic tribes to have names that end with the suffix -ones, but never with -oses, so the spelling Eudoses is suspicious. The Saxones, Teutones, Gutones and Burgundiones all had names that end with the suffix -ones, and the spelling Eudoses could well be a slightly misspelt form of Eudones.

One of the characteristics of terms that ended with the suffix -ones in the early Germanic languages is that the middle consonant of such terms sometimes underwent a sound change known as Kluge’s law. The suffix -ones is a plural and its equivalent in the singular is just -o with the genitive singular form being -nas. The genitive suffix -nas often caused the consonant that came immediately before it to change its articulation slightly and a genitive singular of Eudones would be expected to become Eutas in early Germanic. The development of d to t due to Kluge’s law may then have spread analogically from the genitive to the nominative forms of the tribal name to produce the term Eucii recorded in the early sixth century by King Theudebert.

The name of the Jutes seems likely to have developed from the older form Eudones, becoming Eutii and then Iuti in much the same way as the name of the Goths (Latin Gothi) developed from an earlier form Gutones. It has long been considered unclear why the change from Eudoses occurred, but the name of the Jutes appears to derive from a root eu- meaning ‘help, aid’ also reflected in the runic term auja ‘benefit, luck’. The Jutes presumably received their name because they were held to be ‘those who have aid’ and the aid they were supposed to have is likely to have been supernatural, the aid or luck of the gods.

Other runic inscriptions from Jutland sometimes record similar evidence for the nature of the Jutish language as the inscription on the fire steel from Illerup. Golden pendants found at Skonager and Darum record names such as Niuwila and Frohila that cannot be explained as linguistically Norse or Danish, although these finds date from just after the period of the Anglo-Saxon migrations. Danish linguists generally just pass over evidence like this, unsure of what to make of it. But it is quite obvious what is happening if the Jutes spoke a language that was ancestral to English and not to Danish.

Danish archaeologists typically link the Jutes with a material culture that was native to the central Jutland peninsula. To the north lay the people known as the Cimbri and to the south evidence has been found for another culture that archaeologists named after the settlement of Over Jerstal. By the end of the second century, the Jutes seem to have absorbed the Over Jerstal culture, bringing them into direct contact with the Angles. But by the time that the inscription on the fire steel from Illerup was made, both Jutland and Angeln had become subject to periodic attacks from the east – attacks by the Danes. Gradually Danish power expanded west, until all of the Jutland peninsula was absorbed into the burgeoning Danish kingdom. By the sixth century, the only remaining Jutish kings were those who ruled parts of Britain.

Cimbri? Oh great - now I have to chase them home…