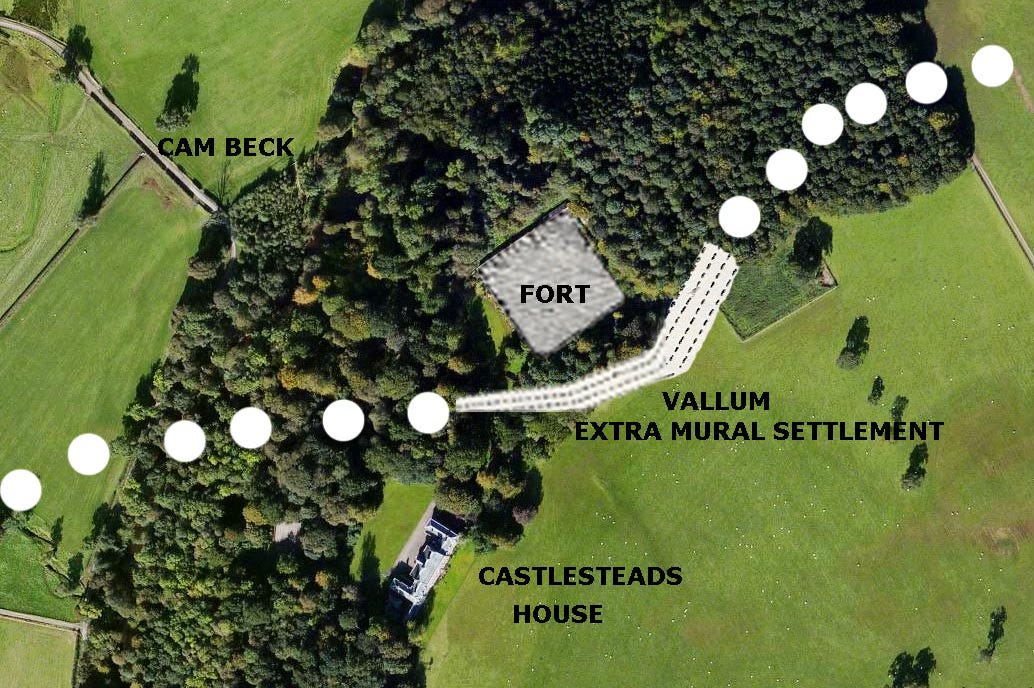

The chief villain of the Arthurian romances is Mordred – or Modred as he was originally known. French authors put an additional r into his name, but Modred is one the few Arthurian characters who was clearly a historical figure. He is recorded in the Welsh annals dying along with Arthur at a battle in 537 at a place called Camlann. Since the 1930s, the site of the battle, traditionally called the ‘Strife of Camlann’, has been associated with Camboglanna, the Roman fort at what is now Castlesteads on Hadrian’s Wall.

It is obvious from the later Welsh stories about the Strife of Camlann that Welsh poets did not know where Camlann was. The conflict was held to be a great tragedy with few known survivors, although the Welsh annals do not make it clear that Arthur and Modred killed each other at the battle. Translated into English, the entry for 537 in the oldest surviving copy of the Welsh annals reads:

Strife of Camlann in which Arthur and Medraut fell. And there was a mortality in Britain and Ireland.

Modred is called Medraut in the oldest surviving copy of the Welsh annals, but Modred in the later versions. How the two different spellings of his name arose has long been unclear, although it is quite evident from a linguistic perspective that Medraut is a textually corrupt spelling, much as the Welsh name Myrddin appears to be a nativized form of Merlin. Modred is a late form of the Roman name Moderatius and Medraut seems to be a slightly modified form of Modred.

The mortality of 537 was long held by historians to be the result of a plague and not to have anything to do with the Strife of Camlann. But the mortality is now recognised to have occurred after the volcanic winter of 536 and to have been caused by famine. Scientific studies have shown that dust thrown up into the atmosphere by a series of volcanic eruptions made the sun seem to dim for much of 536 and the unusually cold weather saw crops fail and famine break out in many parts of Europe. The mention of the mortality of 537 is one of the clearest signs that the entries that mention Arthur in the Welsh annals are reliable. But does that really mean that Modred and Arthur were on opposing sides at the Strife of Camlann?

Another battle mentioned in the Welsh annals that records two people dying suggests that Arthur and Modred were on opposing sides. In 644, the Welsh annals feature an entry that reads:

Battle of Cocboy in which Oswald king of the Northmen and Eawa king of the Mercians fell.

The Battle of Cocboy is called the Battle of Maserfeld by St Bede in his Ecclesiastical History, and Oswald of Northumbria and Eawa of Mercia were on opposing sides. Eawa was a brother of King Penda of Mercia and St Bede also records that King Oswald of Northumbria died in the battle. If the entry for 537 is read along with that for 644, it seems fairly clear that Arthur and Modred were held to have fought against each other at Camlann.

But what were they fighting over? The most obvious answer is that a conflict had broken out during the famine of 537 and that the Strife of Camlann was fought over who should have access to stores of grain. The explanation recorded by later authors is much more fascinating, however, and how it is likely to have emerged seems to be revealed by etymological analysis.

In Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain, Modred is recorded to have usurped his uncle’s throne and seduced his queen Guinevere (or Ganhumara as Geoffrey called her). Where Geoffrey got the idea that Modred had seduced Arthur’s queen from has long seemed impossible to determine. But it is generally recognised that the name Gwenhwyfar, the Welsh form of Guinevere, is cognate with that of Findabair, a princess mentioned in the Irish tale Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley). Both of the women bear a name that literally means ‘white ghost’ in the Celtic languages and they have similar roles in each of the stories.

Táin Bó Cúailnge is an epic tale that hails the feats of the great Irish hero Cú Chulainn as he defends Ulster from the warriors of Connacht. Findabair is a beautiful princess who warriors can only marry if they defeat Cú Chulainn, an impossible task. Female ‘white ghosts’ are widespread in European folklore. Often called ‘white ladies’ by folklorists, they are typically women associated with a tragedy and whose ghosts haunt the place where the misfortune occurred. Both Guinevere and Findabair seem likely to be folkloric characters who first became associated with the stories of Arthur and Cú Chulainn in similar manners.

Guinevere is undoubtedly a tragic figure in the Arthurian romances. But how she became associated with Arthur and Modred is less clear. In Welsh tradition, the Strife of Camlann broke out after Guinevere had been slapped by her sister Gwenhwyfach. But the story related by Geoffrey of Monmouth is much grander.

In Geoffrey’s account, the Strife of Camlann occurred because of a love triangle. Yet how did he come up with the idea?

It was common for medieval poets to conjure up stories from etymological explanations of the names of people. The process is called etymological aetiology by literary historians and it seems to explain how Modred came to be associated with seducing his aunt in Arthurian tradition. Speakers of Welsh would not have known that Modred was a name of Roman origin, but are likely to have tried to interpret it as derivationally Welsh – and the words in Welsh that are closest in form to Modred are modryb ‘aunt’ and modrwy ‘finger ring’. These would naturally suggest to a medieval poet that Modred had an important aunt and that his death opposing Arthur at the Strife of Camlann had something to do with marriage.

It seems very likely that the story of Modred seducing his aunt and attempting to seize Arthur’s throne was invented by a poet employing etymological aetiology. Like her Irish namesake Findabair, Guinevere seems to have been a mythological character first brought into the tale of Arthur and Modred because their deaths at Camlann were considered to be a great tragedy. Arthur was the greatest king of Britain and his death at the Strife of Camlann was the final event of a golden age. His reign ended in the year of a great famine and it saw the collapse of the peace between the Britons and the Saxons that had held for so many years after the celebrated British victory at the Battle of Mount Badon.

Fascinating how linguistic evolution plays into narrative development. Now I wonder how many perceived ‘moral failings’ in legendary figures were retroactively invented through philological misunderstandings or poetic license. As for the famine of 537, that gives a more plausible historical backdrop to the Strife of Camlann than the later love triangle trope, which seems almost quaint in contrast. Perhaps we’re looking at a myth built on bread, not betrayal.

It's amazing how the climate data was used to verify the history. The historians and the scientists seem like separate groups. How well do they work together?