The Historia Brittonum records that Arthur won twelve battles and they are the most controversial evidence recorded about him. All sorts of contentions have been raised about the list of battles – where the battles may have occurred and whether the list is reliable. Some of the sites recorded for the battles can be identified, but no supporting evidence has been discovered by archaeologists at any of the locations mentioned in the battle list. This is not particularly surprising, however, as most archaeologists don’t even try to find evidence of battles from the Arthurian period.

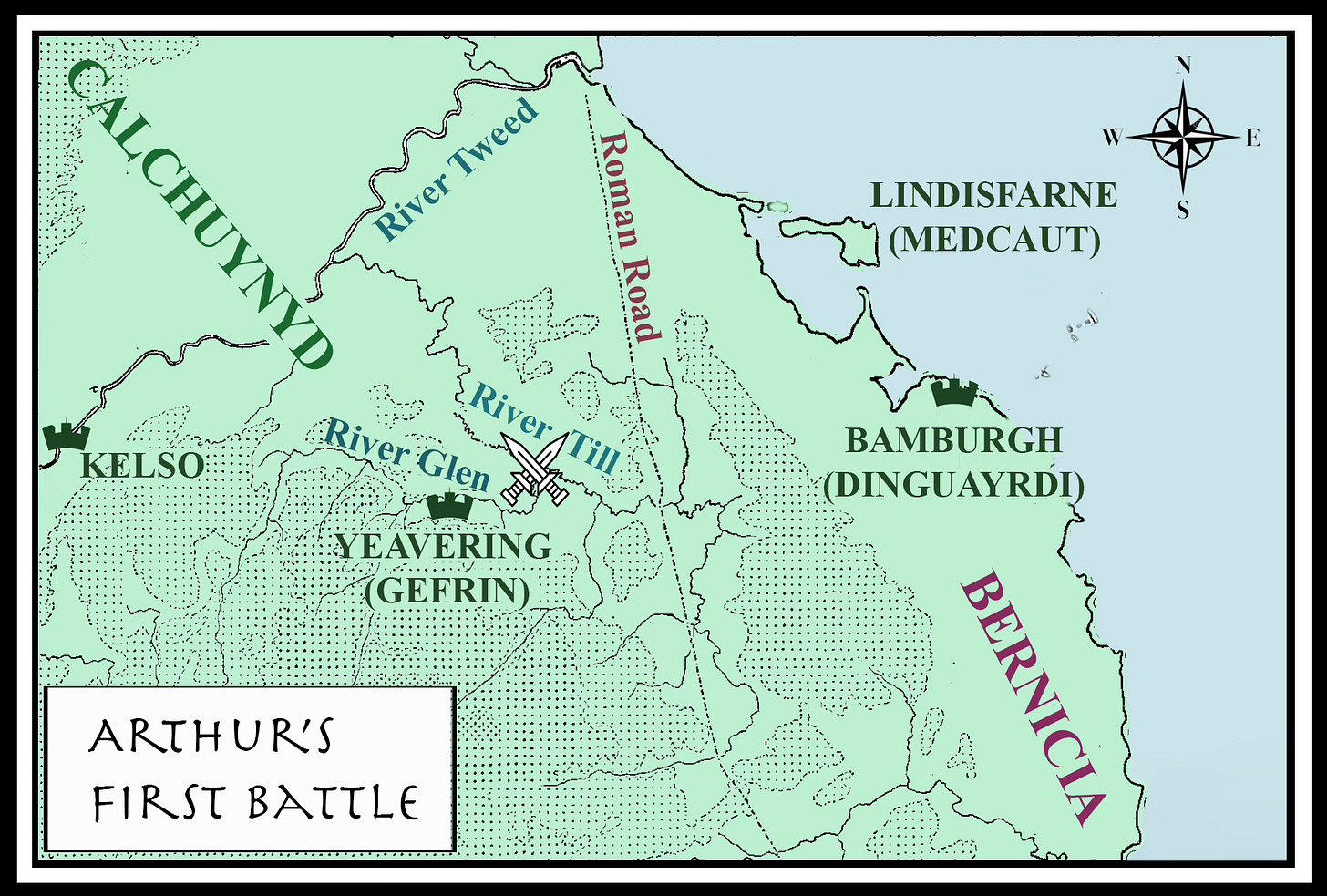

The first of Arthur’s battles is recorded to have occurred at the mouth of the River Glein. It is usually assumed that the river concerned is the Glen in Northumberland as it is in a part of Britain that the Anglo-Saxons did not conquer until the middle of the sixth century. The Historia Brittonum records that King Ida of Bernicia joined a place called Dinguayrdi to Bernicia, and Dinguayrdi is usually accepted to be Ida’s later capital at Bamburgh, a site on the Northumberland coast 16 miles east of where the River Glen flows into the River Till.

The River Glen is also mentioned by St Bede in the second book of his Ecclesiastical History of the English People. In 627, St Paulinus of York washed himself in its waters after preaching at Gefrin, the site of a villa of King Edwin of Bernicia. The Glen runs into the Till near Yeavering, a village in Northumberland where since the 1950s three different excavations have occurred. In 1957 a monument was erected by the road at Old Yeavering commemorating St Paulinus’s visit while archaeologists were still excavating the site of Anglo-Saxon Gefrin. But no attempt has ever been made to excavate the area near the mouth of the River Glen.

The site of the Anglo-Saxon settlement at Old Yeavering lies just north of Yeavering Bell, an ancient hillfort strategically located in the foothills of the Cheviot Hills, not far to the south of Berwick on Tweed and the English-Scottish border. It is quite obvious why a battle would have been fought nearby in the early sixth century, but archaeologists have never seemed interested in the possibility that Yeavering may have had anything to do with Arthur. Instead, the find report of the excavations at Yeavering published in the 1970s stresses that the evidence for occupation at Gefrin indicates how harmonious Anglo-Saxon rule was. Many British archaeologists seem to think that the main reason that the public pays their salaries is for them to try to demonstrate how nice and civilised the Anglo-Saxon invasions must have been.

Gefrin is a derivationally Celtic name, but there is no mention of Arthur and his battles in the Yeavering find reports. The site was located first in the 1940s by aerial photography and immediately associated with St Bede’s description of St Paulinus’s visit. Yeavering Bell seems to have been an old stronghold of the Gododdin, the people whose disastrous attack on the Saxons is remembered in the Old Welsh poem of the name. Arthur is even mentioned in the Gododdin, although only in an aside that notes that one of the warriors of the Gododdin ‘was no Arthur’. The battle of the River Glen presumably saw Arthur allied with warriors from the Gododdin attempting to resist Anglo-Saxon invaders in the days before Ida conquered the area. Their kingdom may have been called Calchuynyd, a realm ruled by a figure called Catraut according to a much later Welsh genealogy. Calchuynyd is also mentioned in a Welsh poem in the Book of Taliesin and it has been connected with Kelso (which was earlier called Calchow), west of Yeavering in the Scottish Borders.

The excavations at Yeavering Bell indicate that the hillfort was abandoned after the Roman invasion. The Gododdin were known to the Romans as the Votadini, an earlier form of the name of the tribe that literally means ‘those who melt down’. Their name presumably reflects a reference to smelting – the skill of the tribe at ironworking or their use of precious metals. Yeavering Bell is literally the ‘bell(-shaped hill) of Gefrin’, with the earlier G- becoming Y- in Modern English, and Gefrin was probably called something like Gabrinum in Roman times, a settlement name derived from the Celtic term for ‘goat’.

The excavations from 1953-1962 were well funded and even saw the preparation of reconstructions of what early Anglo-Saxon Yeavering presumably looked like. But no reference to the battle list of the Historia Brittonum intrudes into what otherwise seems to be an exhaustive find report. Life at Gefrin seems to have just been too frightfully jolly:

at Yeavering, Anglo-Saxon authority is seen from the very outset to have respected native tradition … where actual or latent hostility would be expected to have left its strongest mark, there is not so much as a hint of any discord. The local picture … is of a harmonious relationship between the native population and a minute, governing Anglo-Saxon élite … All the evidence would be consistent with the proposition that what is at issue was an English overlordship which, from a very early stage, had been found mutually convenient and congenial.

Over the next few decades, this statement in the Yeavering find report would be repeated again and again – that there was no archaeological evidence of a violent Anglo-Saxon takeover. Archaeologists started to deny that the testimony of sources such as Gildas was reliable. The historical accounts made it clear how violent and destructive the Anglo-Saxon conquest had been, but an increasing number of archaeologists began to claim that they knew better. The pacifistic Yeavering view grew in popularity, expanded and amplified, until it was shown to be comprehensively wrong by DNA analysis. What too many archaeologists wanted to be true had gotten in the way of the facts.

Not all British archaeologists are hopeless peaceniks of course, but they have generally struggled to find any evidence for warfare or battles from the Arthurian period. A comprehensively vanquished people might be expected to give up their language and culture. They would not continue to struggle after all their warriors had been massacred and the rest of the population demoralised. The key question, however, is where would you look for signs of resistance to the Anglo-Saxon takeover?

Some skeletons of warriors killed in 613 at the Battle of Chester have been recovered. Historical reports describe the bloody massacre that year as a Northumbrian army defeated the Welsh. But similar evidence is lacking for any of the other battles from the sub-Roman period mentioned in historical accounts. Excavations are time-consuming and any evidence for the Battle of the River Glen may well have washed away centuries ago. British archaeologists are usually just not willing to spend any of their time looking for evidence of old battles, least of all those associated with a figure like Arthur.

The reason why there has never been archaeological confirmation of any of the battles associated with Arthur may simply be that so few British archaeologists have ever bothered to look for it. Most of the battles in the list in the Historia Brittonum seem to have occurred at strategically significant locations, but it is not likely that any more evidence will be discovered about them until British archaeologists change their minds about the historical importance of early battle sites.