An exhibition held from 2019-2020 at museums in Hanover and Brunswick declared that the ancient Saxons were a myth. Supported by archaeologists from Lower Saxony, you would like to think that the curators of the exhibition had a strong basis for the claim. The key contention of the exhibition was that the term Saxon only started being used of the people of Lower Saxony during the sixth century. The exhibition claimed that the term Saxon was originally adopted to refer to rebels who refused to acknowledge the overlordship of Frankish kings. Apparently, the rebels of Lower Saxony adopted the name Saxon as a sign of resistance. But is this historical claim valid? And does it have any ramifications for understanding the origins of the Anglo-Saxons?

In the middle of the second century, the Greek geographer Ptolemy issued a description of the known world which included the names of the peoples of Germany. In the lower valley of the River Elbe, Ptolemy situated a tribe who are called the Saxones in most of the manuscripts of his work that have survived. He also called a group of islands near the mouth of the River Elbe the Saxon Islands.

But some of the manuscripts of Ptolemy’s Geography don’t record the name as Saxones. They record it instead as Axones. In 2003, the German historian Matthias Springer claimed that this means that the passage in Ptolemy is unreliable and can’t be accepted as evidence.

Most historians accept that the variant spelling Axones is just erroneous with the initial S- omitted by a copyist. After all, medieval scribes often left the initial letter off words when they were making copies of ancient texts. The name of the Roman fort on Hadrian’s Wall that is recorded in inscriptions as Camboglanna is attested in some manuscripts as Amboglanna. It is quite obvious what has happened with Camboglanna and Amboglanna, and it is equally just as obvious what has occurred with Saxones and Axones.

Springer, however, didn’t accept the most obvious explanation of the variant spelling. Instead, he proposed that the description Saxon was an early Roman description of pirates. That is, after all, how the Saxons usually appear in Roman accounts from the fourth and fifth centuries – as pirates raiding Britain and Gaul. Springer assumed that the name Saxon had subsequently been adopted in the sixth century by northern German rebels who had broken away from the Frankish kingdom. The exhibition held at Hanover and Brunswick uncritically repeats his theory of how the Saxons of Lower Saxony received their name without acknowledging that it is based on a denial of the evidence recorded by Ptolemy.

But where did the name of the Saxons originally come from? It is usually claimed that it reflects a derivation of the name of the seax, a long knife or short sword employed by various Germanic peoples from the fifth to the eighth centuries. This is quite unexpected, however, if the Saxons were a people first mentioned by Ptolemy because the oldest long knives of the type have been dated by archaeologists to no earlier than AD 450, not as early as the time of Ptolemy.

Yet the name of the Saxons is obviously derived from an early form of the Old English word seax. The term has cognates in all the Germanic languages – including Old Saxon sahs ‘knife’ and Old Norse sax ‘short sword, scissors’ – and that is a sign that the term is much older than the earliest find of the weapon called a seax by archaeologists. The term was evidently used for a weapon employed in the years before the development of the battle knife and, like the related English term saw, it literally just means ‘cutter’.

The name of the Saxons has recently been explained as preserving an archaic type of suffix that indicates possession. The name of the people literally seems to mean ‘those who have cutters’ and it obviously refers to swords.

Danish archaeologists have noted, however, that swords were not widely employed by Germanic soldiers in the second and third centuries. Most of the soldiers in the armies of the day used only spears. Swords were largely restricted to leading warriors and were often decorated with silver and bronze.

The most important finds of weapons employed by the ancient Germanic peoples have been discovered in bogs from northern Germany and Denmark. The bog finds demonstrate that some ancient Germanic soldiers used Roman swords, while others employed similar weapons crafted by northern swordsmiths. The Roman swords sometimes preserve the names of the swordsmiths who made them stamped into their blades and the manufacturers usually have Roman or Celtic names.

Another sign that a sword has a Roman origin is bronze decoration such as a figure of the goddess Victoria or the war-god Mars. These forms of decoration seem to have been added to swords that were given originally to Roman soldiers as a kind of military honour. Owning a sword was evidently a sign that a warrior was a member of the elite, and owning a decorated sword was a sign of particular honour.

Yet the name of the ancient Saxons is not just recorded by Ptolemy. A gravestone held in the Archaeological Museum in Split, Croatia, was raised in memory of a young man called Alogius ‘who is also known as Saxxonius’. The gravestone dates from the third century and the name Saxxonius means ‘from the Saxons’ in Germanic.

Other ancient Saxons are similarly recorded in early Roman inscriptions. The gravestone of a Roman veteran from Kalkar on the Lower Rhine records that his widow was called Ulpia Sacsena ‘Ulpia the Saxon’. The name of the veteran is damaged by a break in the stone and it cannot be read any longer. But the gravestone is also from the third century and the name Sacsena does not make any sense if the description Saxon meant ‘pirate’.

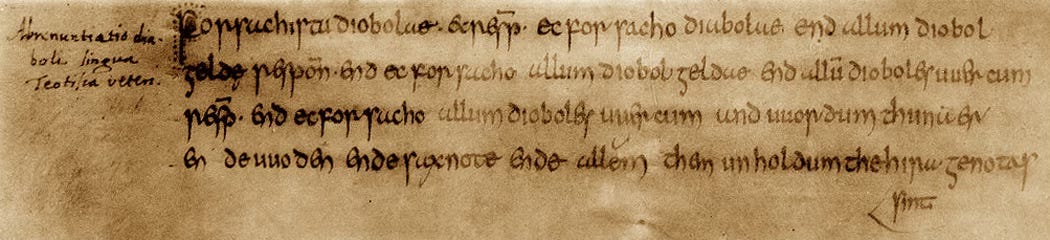

More evidence that the Saxons were a distinct people is known from the religious sphere. Early English tradition held that the kings of Essex were descended from an ancestor called Seaxneat. Most of the Anglo-Saxon kings were held to be descendants of the god Woden, but the kings of Essex were held to descend from a different figure. A continental counterpart of Seaxneat is also attested in an old baptismal vow recorded in a manuscript from Utrecht that was employed to swear off the pagan gods. Written in Old Saxon, the sentence that names the pagan gods reads:

ec forsacho allum dioboles uuercum and uuordum, Thunaer ende Uuoden ende Saxnote, ende allum them unholdum, the hira genotas sint

I forsake all the Devil’s works and words, Thunaer and Woden and Saxnote, and all the spirits that are their companions.

The name Saxnote in the baptismal vow is clearly that of a god of the Saxons and it is linguistically related to Seaxneat of Essex. The name seems to be a very old formation because the Old Saxon o in the second syllable of Saxnote and the corresponding Old English ea in Seaxneat both reflect an earlier au. Seaxneat and Saxnote must reflect the name of a god worshipped by both the East Saxons and the Saxons of northern Germany at a time when their languages had not yet diverged – in other words, during the fifth century or earlier.

Saxnote appears to have been a god worshipped originally in northern Germany before the Anglo-Saxon migrations. The second element of his name is related to Old Saxon genot and Old English geneat ‘companion’, and he appears to have been thought to be a god who accompanied Saxon armies on the battlefield.

Given that only the foremost Germanic soldiers employed swords at first, the name of the Saxons appears most likely to have indicated that they were a warrior elite – that the Saxons descended from a warband who all bore swords. The description Saxon was used in Roman accounts from the fourth and fifth centuries as if it were a term for any kind of raider from northern Germany. But the idea that the Saxons of Lower Saxony adopted their name from an earlier word for pirate is founded on a denial that Ptolemy first mentions the Saxons in his Geography – and it hardly makes sense given the gravestone of Saxxonius, the veteran’s widow Ulpia Sacsena and the god Saxnote mentioned in the Old Saxon baptismal vow.

Really enjoyed this article and its argument. That’s pretty crazy that a museum would make such a claim, when there is more evidence disputing it.

It does raise a question though:

What would be the motivation behind calling the Saxons a myth? My guess is that it is due to the lack of a complete story surrounding their history? Although, I always thought it was mainstream to see the Saxon’s as authentic

history because of similar sources you mentioned (Swords, gravestones and such).

Really interesting essay, thanks for posting 🫡