Before the 1970s, it was widely taken for granted that King Arthur was a historical figure. Most historians accepted that he was historical, the holdouts being considered little more than curmudgeons. But then a range of sceptical voices arose. In the heyday of corduroy and flares, it was loudly proclaimed by English historians that none of the early sources that mention Arthur are reliable.

But the claim was based on poor methodology and it can be shown to be wrong. The earliest mentions of King Arthur in a historical source are two entries in the Welsh annals – or the Annales Cambriae as they are known in Latin. This chronicle records King Arthur leading the Britons to victory in 516 and dying in 537.

The earliest version of the Welsh annals to have survived seems to date to the tenth century, although it includes records of historical events going back as far as the fifth century. No one doubts that the earliest entries in the Welsh annals describe things that really happened. The first entry records that Pope Leo the Great changed the date of Easter in 453 and it is clear from Pope Leo’s letters that he was responsible for the Catholic church adopting the system of the Greek astronomer Meto of Athens for calculating the date of Easter. Similarly, the Welsh annals record that St Patrick died in 457, a date paralleled in some Irish sources.

But how reliable are the entries in the Welsh annals that mention Arthur?

The two entries that mention Arthur can be read simply enough. The entry for 516 states that Arthur fought at a battle that is also mentioned by St Gildas in his sixth-century sermon The Ruin of Britain. St Gildas was a contemporary of Arthur, although the Welsh annals give the battle a slightly different name:

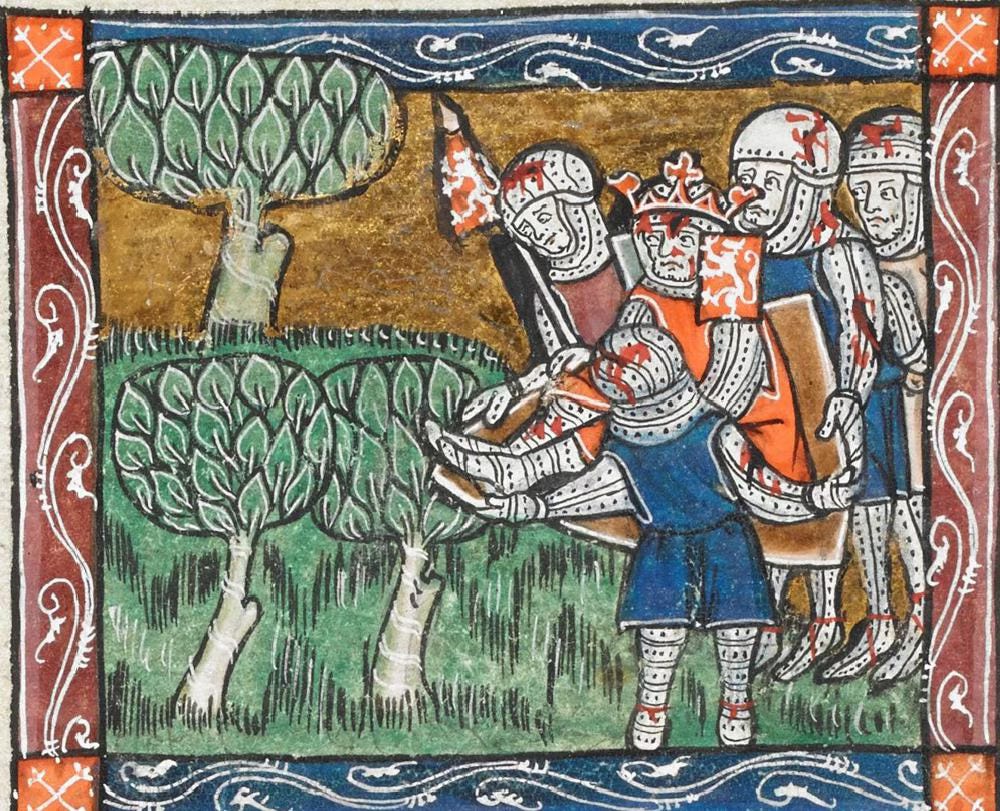

The Battle of Badon in which Arthur bore the cross of Our Lord Jesus Christ for three days and three nights upon his shoulders and the Britons were the victors.

Given that St Gildas records that the battle at what he calls the Badonic Mount involved a siege, the battle could well have lasted for as long as the Welsh annals record. But what about Arthur bearing a cross on his shoulders? What does that mean exactly?

The description of Arthur bearing a cross on his shoulders appears to be a recollection that the brooch on his cloak was decorated with a cross. Brooches decorated with crosses were fashionable during the fifth and early sixth centuries, indicating that the entry for 516 is unlikely to be a much later concoction.

The entry for 537 in the Welsh annals is less difficult to interpret. It records a ‘strife’ or battle where Arthur died along with another figure – and that mortality (mortalitas) also occurred that year:

The strife of Camlann, in which Arthur and Medraut fell. And there was mortality in Britain and in Ireland.

The mortality recorded in the entry for 537 is now widely accepted to have resulted from the disruption to agriculture caused by the volcanic winter of 536. Scientific evidence supports the observations recorded in Roman sources at the time that the sun’s rays were particularly weak for much of 536. The weakness is now known to have been caused by a veil of dust produced by volcanic eruptions, and it caused crops to fail right across Europe that year.

The two records that mention Arthur in the Welsh annals can be validated by reference to other historical evidence and they make the scepticism about King Arthur appear quite wrongheaded. Even the Latin that the Welsh annals are recorded in changes over time, the earliest entries betraying characteristic features of fifth and sixth-century date. There is no reason to doubt the veracity of the earliest historical mentions of Arthur.

So what was the main reason for all the scepticism? Were the historians of the 1970s just not very competent? There has certainly been more than enough poor history written about King Arthur over the years. But the root of the scepticism lies in the mentions of Arthur that appear in other early chronicles such as the Annals of Ulster. The earliest surviving copy of the Annals of Ulster dates from the fifteenth century and it includes entries that reach back as far as the fifth century. Yet the Irish annals mention King Arthur in an entry for 467 that reads:

Death of Uter Pendragon, king of England, who was succeeded by his son, King Arthur, who instituted the Round Table.

This entry is clearly anachronistic and influenced by the Arthurian romances. The claim that Arthur’s father was a king of England would not be expected in a record created in the fifth century because a place called England did not yet exist at the time. No one would accept that the entry for 467 in the Annals of Ulster is anything other than a very late addition to the Irish chronicle. The entry is more likely to have been created in the fifteenth century than in a much earlier period.

In contrast, the entries that mention Arthur in the Welsh annals are not clearly anachronistic. Arthur bearing a cross on his shoulders sounds a bit odd at first, but people were known to wear brooches decorated with crosses on them at the time, so the claim in the Welsh annals is far from being unexpected. All that was unexpected was the failure of sceptical historians to recognise what the entry for 516 was describing. A brooch with a cross on it dating from the fifth century has even been held by the British Museum since the 1950s. It is fairly obvious what the entry for 516 records if you realise that brooches decorated with crosses are a characteristic find from the fifth and sixth centuries.

It was also quite simple to demonstrate that the entry for 537 is historical because the Annals of Ulster record that famine struck Ireland in 536. All that the sceptical historians needed to do was to recognise that the reference to mortality indicated deaths caused by famine. Two crucial failures of imagination led two generations of historians to mislead the public about the historicity of King Arthur.

The task for historians should now be to return Arthur to his proper place in British history. Who was the figure who inspired the romances? What did he accomplish? Does he deserve his reputation as the greatest of the kings of Britain? Accounts of early British history will remain incomplete until this is done.

The Age of Arthur now has over 1,000 subscribers, over 1,000 followers and every post is being read over 1,000 times. Thanks to everyone who has helped make this possible over the last year or so.

Fascinating article- thank you. Increasingly, there are evidence for the survival of "pockets of Romantas" into the 5th century and beyond- evidence from Lincoln (St Peter in the Bail), Chedworth Villa room 28 roman mosaics now dated to the fifth century (https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/gloucestershire-cotswolds/chedworth-roman-villa/archaeological-discoveries-at-chedworth-roman-villa) , the Vergilius Romanas (http://www.vortigernstudies.org.uk/artlit/vergilius.htm ), the Thetford Hoard, now dated to the 5th century ( https://the-past.com/news/new-thoughts-on-the-thetford-hoard/) , and Highdown Hill in West Sussex with its 5th century hoard of gold coin at Patching and Roman inscribed glass. Very good to see the intriguing Sussex brooch with its syncretic animal head brooch, cross, and cross bow brooch shape- it is frustrating from the British Museum files that a closer identification of find spot than Sussex could not be made with even a letter from Bruce Mitford in the file!

Fascinating and looking forward to reading the book. What are thoughts now on the mention of Arthur in Y Gododdin where the name Arthur is used as a positive comparison to the dead warriors of The Battle of Catreth?